School language policy in the Union of Myanmar: issues, challenges and prospects

Published on 04/03/2020.

This short article is a (necessarily highly simplifying) synthesis of recent work, and in particular of two articles, published in the Oxford Tea Circle in 2018 and in 2019, as well as a report published by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in March 2020, based on a large number of interviews and enhanced by case studies.

Southeast Asia is a region of the world remarkable for its ethnolinguistic diversity: it is estimated that some 1,250 languages are still spoken there, although around half of them appear to be under threat in the short to medium term.

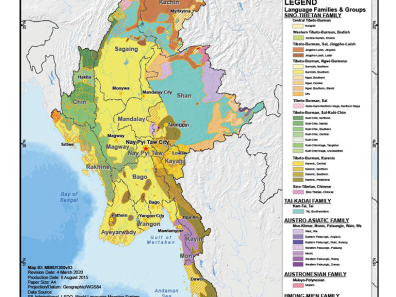

At the crossroads of this region, the Indian subcontinent and the Chinese world, the Union of Myanmar (Burma before 1989) is one of the countries emblematic of this ethnolinguistic heterogeneity. The official nomenclature (inherited from colonial censuses and now widely debated) recognizes 135 indigenous groups ( တိုင်းရင်းသား ). The national language, Burmese, is mastered to varying degrees by almost the entire population, but it is estimated that around 120 languages are spoken throughout the country, particularly in the mountainous regions that make up the periphery of the national territory.

Managing this diversity has been a central issue throughout the country's contemporary political history, which has been continually marked, since independence was negotiated on supposedly federal foundations in 1948, by conflicts involving dozens of armed groups, largely formed on "ethnic" bases.

Click on the images to see them in larger format.

Towards an evolution of language policy in schools

After several decades of military dictatorship (1962-2011) legitimized by the risk of "disintegration" of the country, Myanmar has embarked on a process of relatively rapid political change, with significant developments in terms of democratization and decentralization. As part of the reform of the education system accompanying this process, many international experts and local activists have recommended or called for the introduction of a Mother Tongue-Based Education (MTBE) system, which would involve a transition in the language of instruction in schools across the country from the local language to the national language, as the school curriculum progresses.

The arguments in favor of such a language policy at school, which echo priorities defined by international institutions such as UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank, are of various kinds. Firstly, to help combat the "erosion of linguistic diversity" that is affecting Myanmar and the rest of the world. Secondly, from an educational point of view, numerous studies carried out throughout the world show that schooling that starts in the students' mother tongue gives better results than abrupt immersion in a national language that is sometimes foreign to them. Finally, on a political level, the inclusion of minority languages in the country's public schools should constitute a strong symbol, helping to project the image of a nation "united in diversity", in contrast to the accusations of "Burmanization" levelled against the central state for decades by numerous organizations linked to ethnic minorities.

Geolinguistic complexities

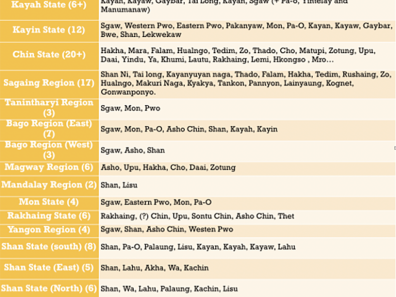

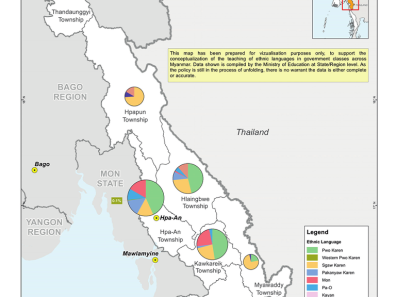

In practice, however, multiple challenges stand in the way of such a language policy at school. The slow but real process of decentralization is not necessarily capable of satisfactorily taking into account the diversity and interweaving of populations on the territory. While the choice of a single language of instruction for elementary school in each of the fourteen States and Regions that make up the Union of Myanmar seems completely unrealistic, the situation is hardly any simpler at the lower levels of the Burmese administrative scale (districts and townships).

In urban areas in particular, even in regions largely populated by minorities, the heterogeneity of pupils in a single school would rarely make it possible to decide on a language of instruction other than Burmese, which is often de facto the pupils' common language and the one they master best. Separating pupils into linguistically homogeneous classes, in the name of educational arguments and essentialist conceptions of ethnicity, seems hazardous at best in a country that has still not emerged from more than seven decades of armed conflict.

Parallel to these issues - and without even mentioning the specific situations of groups that are not recognized as indigenous, such as the Rohingyas or the Nepalis - agreeing on a list of languages to be taught in schools and composing curricula in these languages is not an easy task. The minorities that populate the Union of Myanmar present a wide variety of linguistic situations, with languages that have become more or less standardized throughout history. In many cases, however, diversity on the ground takes the form of a continuum of dialects and a multiplicity of written traditions in different alphabets, linked to a multitude of endonyms and exonyms, which correspond to identities of variable geometry, intertwined and disputed. Introducing minority languages into formal education - particularly in writing - implies a process of discretization and standardization of this continuum.

In a country where ethnic identities are highly politicized (two-thirds of the political parties contesting the 2020 elections are constituted with reference to an ethnonym), the philosophical contradictions underlying this process are reflected in multiple controversies. Indeed, standardizing minority languages in order to better protect them is often tantamount to reducing diversity... in the very name of diversity. This raises the question of the legitimacy of the actors who make up the countless literary committees, and of their ability to agree on common, sustainable linguistic and identity projects.

Particularly uncertain are the futures of "ethnic esperantos" projects, aimed at assembling languages between which intercomprehension is not always possible, so as to create languages corresponding to the mobilization of common ethnic identities (notably among the Nagas, Chins and Palaungs).

A less ambitious but arguably more realistic policy

In such a context, current school language policy, based on a 2014 piece of legislation, provides for minority languages to be taught as subjects (and not used as the language of instruction in which the entire primary curriculum would be written) for a few hours a week. In 2019-2020, 64 languages are being taught across the country (see table, map, videos and illustrations below).

The school language policy currently being rolled out also includes a series of measures to ensure that more minority teachers are trained to use these languages orally, so that they can "explain" the national curriculum written in Burmese, and thus reduce the difficulties that pupils from non-Burmese-speaking families may face.

In the context of the multiple, profound and sometimes dramatic difficulties linked to the politicization of ethnicity in Myanmar (and not forgetting the crucial but separate issues of education systems linked to armed groups on the one hand, and populations denied Burmese citizenship on the other) this language policy seems to us to be relatively well calibrated for the years to come. It forces the players involved to negotiate with each other about their linguistic and identity projects, while avoiding raising the stakes prematurely. Although its implementation is still too recent to be able to assess its results, this policy is likely to have positive consequences, both educationally and politically; it will prefigure, perhaps, more ambitious projects in the medium and long term, in parallel with the evolution of these issues in Southeast Asia and around the world.

Nicolas SALEM-GERVAIS

Lecturer in the Burmese section

Research areas: nation building processes, education, language policy