Quechua oral numeration and its writing in quipus

Quechua and oral numeration

The name Quechua refers to a family of languages/dialects now found in five South American countries: Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Argentina, with a total of over seven million speakers, most of them in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador. Quechua was an unwritten language in the canonical sense of the term.

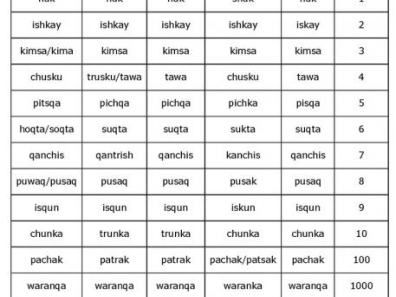

The oral Quechua numbering system refers to cardinal numbers. Cardinals are expressions that express a precise quantity: one, twenty-two, three hundred and five, whose essential semantic function is counting. Quechua has two types of cardinal: simple and compound. The simple ones are used to form compounds, and number thirteen (Table 1).

We can see from this table that this is a decimal-based numeration. The first nine terms correspond to units, from one to nine, chunka (ten) is the base, the other three terms are powers of ten: pachak (hundred), waranqa (thousand), hunu (ten-thousand or one million, depending on the source). For the value "four", two expressions are possible: chusko, characteristic of Quechua QI, while tawa belongs to Quechua QIIC. The numeral hunu is associated with ten thousand in the earliest grammars and chronicles (16th century and early 17th century). It's only in later dictionaries, describing Quechua associated with the QIIC branch, that the term hunu appears in association with one million. We consider that this evolution is probably due to the Spanish influence, which moves from the simple numeral mil (one thousand) to the following one millón (one million): in the Spanish language, there is no simple term to express ten-thousand. However, hunu remains associated with ten-thousand in grammars describing the Quechua variety of Ecuador, called Quichua, from Nieto Polo's very first published in 1753 to contemporary grammars.

Compound cardinals are formed from simple cardinals and can canonically express any other number up to ten-thousand or one million and beyond. These numeral syntagms are structured around chunka (ten), which is the basis of the system, and its powers pachak, waranqa and hunu, following the usual rules of addition and multiplication, Greenberg (1978: 257-258). A detailed study of the characteristics of Quechua oral numeration and its relationship with Aymara oral numeration can be found in Gonzalez (2020).

The quipus

The Quechua word quipu[2], meaning knot, appears in early dictionaries as an expression related to counting and calculation, Table 2.

.

The use of the quipu in the pre-Columbian Andean region appears to be very old, but its beginnings remain unknown. Some twenty quipus currently on record have been identified as belonging to the pre-Inca Wari culture of the Middle Horizon period, 600-1000 AD

But it was in the Inca Late Horizon period (~1400-1532 AD) that the quipu reached its greatest development and diffusion, and a standard model developed. Information on Inca quipus is more extensive thanks to the testimonies of early colonization chroniclers (16th and early 17th centuries) and archaeological evidence. Today, over 900 Inca quipus can be found in museums and private collections around the world, almost all of them listed in the Khipu Database, created by Urton in 2002[3]. Most of these quipus come from the coast of Peru and northern Chile, due to the dry desert conditions that have favored the good preservation of the plant and/or animal fibers that make up these artifacts.

In the Inca period, the quipu was used as a privileged recording tool. Many chroniclers refer to quipus as "registers", "accounts", "memoirs". The information encoded in the quipus, according to these chroniclers, covered the political and economic spheres: population census, tracking of tributary obligations, services lent to the state in the form of corvée (mita in Quechua); but also religious: ritual calendars; and historical: myths, the genealogy of sovereigns and the songs that commemorated them.

The standard Inca quipu

In the most general sense, the term quipu refers to a textile construction made of non-braided, but twisted ropes of cotton or camelid fibers (llama, alpaca, guanaco and vicuña). Most quipus also include knots, and the ensemble of ropes and knots can show a structure with spatial and colorful patterns.

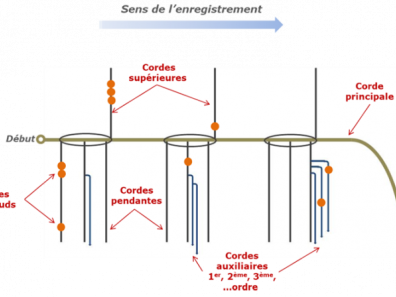

As shown in figure 1, the standard Inca quipu is composed of a transverse rope called the main one, wider and longer than all the others. At one end of this main string, there is frequently a pompom or bundle of fibers that signals the start of information recording, and at the other end, there is more of an extension of the main string. The cords attached to the main cord are called pendant cords (downward-facing) and superior cords if they are upward-facing. There are also auxiliary strings attached to a pendant, a superior or another auxiliary. The latter is referred to as a second-, third- or even higher-order auxiliary string.

The strings

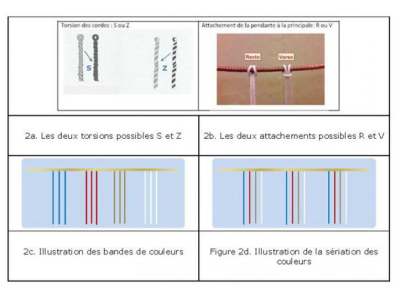

All the strings making up an Inca quipu are characterized by their color, the direction of twist and, in the case of hanging strings, their type of attachment to the main string. Strings can be of a single color or of several (spiral, marbled, etc.). In most cases, dangling strings are distributed along the main string, forming spatial and color patterns. Two color patterns appear frequently: stripes and seriation. All these features are shown in figures 2a, b, c, d.

In Figure 3, we show a quipu from Nazca in the Musée du Quai Branly collection, made up of 179 hanging strings distributed in 33 groups of 7, 6 and 5 strings. The window in red indicates the groups with 5 strings, with the following serialized color patterns: white, white, white, brown, brown.

The red window indicates the groups with 5 strings, with the following serialized color patterns: white, white, white, brown, brown.

Knots

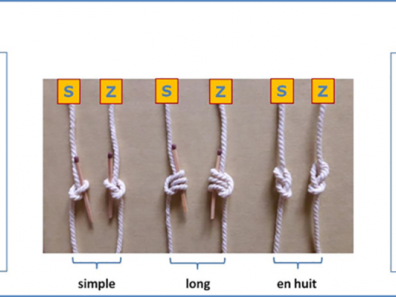

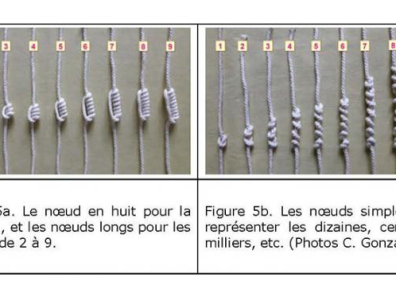

Knots, tied into the rope itself, are present in most Inca quipus. In the early 20th century, Locke (1923), studying three quipus from north of Lima, revealed how the knots encoded the Quechua cardinal numbers in a quipu. According to him, the numbers were written on the hanging or upper or auxiliary strings, using three types of knot: figure-of-eight, long and simple. Urton (2003: 74-88) noted the need to take into account for each type of knot, the two possible orientations S and Z. Figure 4.

Also according to Locke, the figure-of-eight knot represents the numerical value 1, while the long knots represent values from 2 to 9 depending on the number of times (passes) the cord was wound on itself before being tied in the long knot (figure 5a), and the single knots will represent tens, hundreds, thousands, etc. (figure 5b).

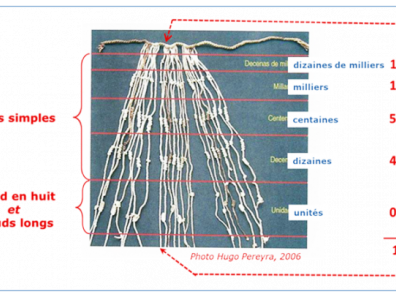

The Inca numerical quipu

The Quechua numerals[4] are written as follows: the knots are placed at different levels of each hanging string; thus, as a whole, the quipu has horizontal rows of knots located at approximately the same height. The lower level, furthest from the main rope, corresponds to the units. The next level, moving upwards, corresponds to the tens, and so on for the levels of hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands, getting closer and closer to the main string. Figure 6 shows a quipu from the Pachacamac Museum, in which five horizontal rows of knots can be distinguished, ranging from units to tens of thousands, and one of its hanging strings reads 11,540. The absence of units in this number is indicated by the absence of a knot. This writing of Quechua numerals in quipus uses decimal positional numeration.

These so-called "numerical" quipus account for roughly two-thirds of the Inca quipus currently recorded. However, while we know how to read all the numbers recorded on them, we don't yet know how to fully interpret what they referred to.

Some numerical quipus show mathematical relationships of addition and multiplication, subtraction and division, fractions and proportions. The work of Ascher and Ascher (1981) and Chirinos (2010), among others, is particularly important in this field. Also, all the non-numerical physical characteristics of strings and knots mentioned above are part of the information conveyed by the numbers written in quipus. Significant advances have been made over the last twenty years in the interpretation of Inca numerical quipus, by integrating numerical and non-numerical data in the interpretation.

Three exceptional Inca quipus

Figure 7 shows a quipu, of unidentified origin, housed in the Musée du Quai Branly, composed of 64 hanging strings distributed, along a 107 cm main string, in 14 groups with 3, 4, 5, 6 or 7 strings per group. There are also 15 auxiliary strings distributed non-uniformly among the pendants. This quipu exhibits the two highest numerical values ever encountered to date: 320,535 and 105,552, at the very beginning of the recording.

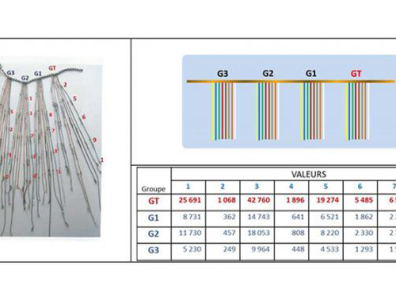

Figure 8 shows the AS120 quipu from Ica, in the Berlin Ethnological Museum, studied by Ascher and Ascher (1981) and Chirinos (2010). The quipu consists of a 107 cm-long main string, 32 pendant strings and 4 auxiliary strings. The pendant strings are distributed in 4 groups of 8 strings each, and each group carries an auxiliary string. All groups show the same color pattern in series. The values of the GT group are the sum of the values of the G1, G2 and G3 groups, position and color by position and color. The authors have demonstrated proportional relationships between total values (GT) and partial values (G1, G2 and G3) recorded in pendant and auxiliary strings. Other quipus show the same characteristics.

In 2014, some thirty quipus were discovered for the first time in an Inca warehouse, collca in Quechua, in the archaeological site of Incahuasi (Cañete). These quipus were found alongside products such as peanuts, chillies and black beans, and their study enabled Urton and Chu (2019) to put forward the hypothesis of the existence of a tax system applied to the products stored in this collca. Figure 9, describes two quipus from this collection: UR267A and UR267B, found alongside chillies.

Working on the numerical values of the nodes, the orientation (R or V) of the pendant attachment and their color patterns, Medrano and Urton (2018) have managed to match the content of a colonial document with an archive of post-Inca quipus from the Santa Valley (Ancash). Also, Hyland (2016) working on more recent quipus from the early 20th century, demonstrates that quipus structured in color bands record data at the individual level (low numerical value) while those structured in color seriation record grouped data (high numerical value).

This latest work on post-Inca quipus combining digital data with non-numeric features provides a springboard for advancing the interpretation of content recorded in standard Inca quipus.

Carmen Gonzalez

Member of the Society of Americanists

Bibliography

Adelaar, W. 2017. "Diversidad lingüística en el Perú precolonial", in J.C. Godenzzi y C. Garatea (eds). Historia de las literaturas en el Perú. Vol. 1. Lima: PUCP.

Ascher, M. and Ascher, R. 1981. Mathematics of the Inca: Code of the Quipu. New York: Dover.

Cieza de León, P. 2005 [1553]. Del Señorío de los Incas. Caracas: Biblioteca de Ayacucho.

Chirinos, A. 2010. Quipus del Tahuantinsuyo. Lima: Comentarios.

Garcilaso de la Vega, I. 2009 [1609]. Comentarios Reales de los Incas. Lima: Edición facsimilar.

Gonzalez, C. 2020. "Numeral systems in Quechua and Aymara: a history of suffixes". Faits de Langues, 51(2), 15-38.

González Holguín, D. 1608. Vocabulario de la lengua general de todo el Perú, llamada lengua Quichua o del Inca. Lima: F. del Canto.

Greenberg, J. 1978. "Generalizations about numeral systems", in J.H. Greenberg, C.A. Ferguson & E.A. Moravcsik (eds). Universals of Human Language 3. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hyland, S. 2016. "How Khipus Indicated Labour Contributions in an Andean Village: an Explanation of Seriation, Colour Banding and Ethnocategories." Journal of Material Culture, 21(4), 490-509.

Locke, L. 1923. The ancient quipu or Peruvian knot record. New York: The American Museum of Natural History.

Medrano, M. and Urton, G. 2018. "Toward the Decipherment of a Set of Mid-Colonial Khipus from the Santa Valley, Coastal Peru." Ethnohistory 65(1): 1-23.

Nieto Polo, T. 1999 [1753]. "La Breve instrucción, o Arte para entender la lengua común de los indios, según se habla en la provincia de Quito". In Cuatro Textos Coloniales del Quichua de la "Provincia de Quito". Quito: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

Parker, G. 1963. "La clasificación genética de los dialectos quechuas". Revista del Museo Nacional, 23: 241-252.

Pereyra, H. 2006. Descripción de los quipus del museo de sitio de Pachacamac. Lima: CONCYTEC

Santo Tomas, D. 1994 [1560]. Vocabulario de la lengua general de los indios del Perú, llamada Quichua. Madrid: Edición Facsimilar.

Torero, A. 1964. "Los dialectos quechuas. Anales Científicos de la Universidad Agraria, Lima, 2(4), 446-78.

Torero, A. 1974. El quechua y la historia social andina. Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma.

Urton, G. 2003. Signs of the Inka Khipu. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Urton, G. and Chu, A. 2015. "Accounting in the King's Storehouse: the Inkawasi khipu archive". Latin American Antiquity, 26(4), 512-529.

Urton, G. and Chu, A. 2019. "The Invention of Taxation in the Inka Empire". Latin American Antiquity, 30(1), 1-16.

Notes

[1] The Quechua language family is a textbook case in terms of the strong dialectal variations from one region to another and the difficulty in determining clear boundaries between them, and consequently in establishing criteria that clearly distinguish a language from a dialect. The debate on the subject remains lively to this day. According to linguists Parker (1963) and Torero (1964), Quechua as a whole can be broken down into two major groups (QI and QII, following the nomenclature proposed by Torero), each made up of dialects with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Between the two groups, the degree of linguistic differentiation does not allow speakers to understand each other. According to modern linguistic criteria, a large proportion of these dialects should be designated as separate languages (Adelaar 2017).

[2] In Quechua literature, we find several spellings for the word knot in Quechua: quipu according to the standard Spanish orthography, khipu according to the Southern Quechua orthography (Cusco-Bolivia), kipu according to the Central and Northern Quechua orthography (Ecuador). In this contribution we write quipu and to express the plural, quipus.

[3] Khipu Database: https://web.archive.org/web/20210126031628/https://khipukamayuq.fas.harvard.edu/

[4] A numeral designates and/or represents a number or arithmetic numbers. The "Numeral System" is the organization of linguistic expressions used to denote numbers.