Explorers #3: Richard Collasse's account of a temporary monk in Japan

Foundation

As part of the "Les Explorateurs" project, Richard Collasse shared the story of his life as a temporary monk in Japan. After a long career as CEO of Chanel in Japan, Richard Collasse decided to take a few months off before resuming activities as Senior Adviser in various companies, teaching at leading business schools in France, the Middle East and at a Japanese university, and joining the Board of Directors of a major Japanese company.

On this occasion, at the beginning of January, he moved into an old traditional "machiya" in the north of Kyoto city and then joined the Za Zen Shinju-An Buddhist hermitage as a "temporary monk", a fictitious title granted to him by the High Priest who runs the temple. Since then, he's been helping with hermitage tasks such as cleaning the centuries-old moss gardens and maintaining the buildings, all the while indulging in Za Zen practice.

Find out more about Richard Collasse's posts!

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 1

December 31, 2023.

This is not just another year coming to an end for the author of these lines. It's an essential moment in his life, that famous retirement that so many people look forward to, but which for his part he dreads. The very word "retirement" revolts him. He associates it with the Russian Retreat, a catastrophe, destitution, the shame of idleness, institutionalized laziness, perhaps even the antechamber to death. As far back as he can remember, he has always worked and found deep satisfaction in toil. He has piled up duties like others pile up plates, and found ways to speed up movement, awaken somnolence, shake off inertia, leap over obstacles, knock down all the "Impossible" that Japan delights in putting in the way of an out-of-the-ordinary project.

Bref, for the Japanese he's a "Maguro", a tuna, that fish that dies if it doesn't swim.

His Japanese wife feared he would become one of those "Nure Ochiba", an autumn leaf that has fallen to the ground, wet after a rain, that sticks to the soles without being able to get rid of it, in other words, one of those husbands who are so distraught when they've left their business that they follow their wife's shadow - Ikebana, tea ceremony, traditional buyo dance, French cooking lessons, fine lunches with friends. If he were Japanese, he might even be treated like one of those cumbersome Sodai Go mi objects kicked out of their own home after thirty-five years of loyal service.

To avoid all this unpleasantness, he decided he would cope with the breakup by taking a buffer time, a three-month buffer to break the rhythm, before resuming new activities. His wife had suggested a trip. He replied:

"Yes, we're going on a trip, but an immobile one."

Because "Retirement" for retirement, he figured he might as well make it a real one.

He chose Kyoto to live out these three months.

He became a "temporary monk" there, humbly inviting the reader to accompany him on his wanderings.

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 2

Kyoto

In my fifty years in Japan, I've probably been there over three hundred times. In the early days of my life here, I'd rush over as soon as a long weekend opened up. I'd wander aimlessly through the alleys of the residential quarters; I'd daydream in the stone and moss gardens that few tourists visited; I'd fall in love with the silhouette of a young woman in a kimono whom I followed through the snowy lanes behind the Nanzen-Ji (南禅寺). Later, I accompanied friends and visitors there, negotiating with local department stores. I lived an extreme passion.

But I never stayed more than two nights in a row.

So it was Kyoto that I chose to live these three months of vacuity.

My friends recriminated, it's so cold there in winter that I wouldn't last more than three weeks and I couldn't bear to stop "swimming" at my usual frantic pace. My wife recriminated that she could never live there, as being a pure Edokko (江戸っ子) she would feel like a foreigner in her own country....

We arrived on January 10 at the house lent by a Japanese friend in Kyoto's "Kita-ku" very close to the Daitoku-Ji (大徳寺), wrongly christened the Maple House because the shrub growing in front is by no means a "Momiji" (紅葉), but it does make red leaves all year round, perhaps by mimicry?

Then we realized we were going to have to learn to deal with the cold: it was 6ºc in the street and... 4ºc in the house, which hadn't been heated for several months! So we started by covering up, then lit a friendly "Tōyu" kerosene stove (灯油) which quickly brought the ambient temperature up to 14ºc, a temperature offering, we later learned, comfort considered insolent! We set down a kettle filled with clear water from the house well. The kettle began humming a perky little tune that was to become our nightly companion.

The Provisional Monk was about to embark on his quest for silence and harmony "WA" (和).

The Daitoku-Ji bell rang 5 p.m.

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 3

Daitoku-Ji (大徳寺).

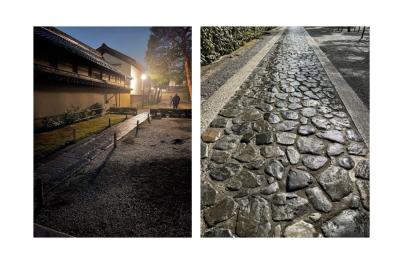

While we're waiting for the house to warm up, let's take a stroll around the grounds of this huge complex of 22 temples and hermitages dotted over 23 hectares.

It is said that the ghosts of the famous personalities who rest here float around at night on the straight paths of the Daitoku-Ji, their landing strips!

As with all self-respecting Japanese, we are firm believers in wandering spirits. In fact, it seems to us that the monk we see at the end of a path is holding an ectoplasm by the hand. We'll never know if it was an illusion in the evening mist, as the monk also disappeared when we approached.

As for me, I'd love to meet the spirit of Murata Jukō, (1423-1502), founder of the tea ceremony, buried in the cemetery of the Shinju-An hermitage (真珠庵) where we're expected tomorrow. I'm less tempted to cross paths with Oda Nobunaga, one of the three unifiers of Japan, whose tomb is further down the road.

Still, we're moved to be walking in this place where the great codifier of the tea ceremony, Sen no Rikyû, lived and allegedly committed suicide by Seppuku on the orders of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the second of the country's three unifiers.

There are many versions of this story, but one thing is certain: we're treading on ground soaked in his blood.

The Daitoku-Ji burned almost to the ground during the Ônin War. The task of rebuilding the destroyed temples fell to the Za Zen monk Ikkyū Sōjun (1394-1481). He entered "the orders" at the age of 13 to learn the discipline of Rinzai Zen; of eccentric reputation, he was an iconoclast, a good drinker, a vagabond for a time, a poet in his spare time; for example, he put an end to celibacy for monks.

The Shinju-An is dedicated to him. He lived there for the rest of his life.

When we get home, a matron is waiting for us, arms crossed and eyebrows furrowed in front of the door. She tells us simply:

"Here, when you go out, you turn off your stove!"

We'll never know how she saw that we'd left the heating on.

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 4

Every morning in our world

I'm not sure what woke me up:

The cold in our tiny room of four tatami mats - just over 6 m2 - as the antediluvian gray tin stove that resembles American surplus offices with its crooked beret went out in the middle of the night for lack of fuel and the room thermometer reads 5º? The thin mattresses on the tatami mats didn't prevent the cold from maliciously seeping in from underneath; the futons piled on top of us, making us look like a layer of strawberries in the center of a mille feuilles, barely managed to retain our body heat. My wife is buried under the futons' wadded-up waves, while I find myself thinking wistfully of our grandparents' nightcaps as I run my hand over my frost-stiffened hair.

Would it be a regular, heady rubbing in the street outside our house that has insidiously penetrated the convolutions of my brain, and which I finally realize is that of an energetically handled broom? Every day from 6:30 onwards, it becomes our relentless alarm clock. We'll soon discover that the zealous roadman is none other than the cantankerous neighbor who chided us the night we arrived for putting the whole "Kita Ku" in danger of falling prey to the flames.

She would later prove to be a thoughtful and helpful grandmother after we politely declined an invitation to share her meal one day when we visited to offer her a bunch of "hikkōshi soba" (literally: move-in noodles) symbolizing the wish for harmonious relationships; these invitations to agape actually crudely signify according to Kyoto codes of decorum: "Well, it's time to clear off. I've got other things to do". Those who eagerly accept are definitely toast!

This doesn't stop him from continuing his vengeful sweeping every morning from the crack of dawn.

We've had to get used to it, and in the end, it's no worse than the mawkish melodies of our Apple laptops!

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 5

The Pearl Hermitage 真珠庵

The weather sometimes works miracles: it's been snowing heavily since morning. When we arrive in the late afternoon at the hermitage, where we'll be spending most of our time copying Sutras and trying to approach "Satori" by assiduously practicing Za Zen, we're treated to the pearly whiteness for which it's named. The founder of the Rinzai-Shū sect, Yōgi Houe, one night while practicing Za Zen, seeing snowflakes glistening in the moonlight on the floor of his hermitage like pearls of mother-of-pearl, so christened his refuge.

The Shinju-An is not open to the public, and as the Daitoku-Ji is too far off the tourist trail, we won't run the risk of bumping into a scruffy, braying American, a Chinese climbing the hundred-year-old pines in search of a selfie, or peeing happily on the garden moss.

We've already met the Shinju-An's reverend. A slow, cautious, year-long approach to seduce him won us his favor. We had a trump card: access to the country's finest sake through Japan's oldest wholesaler, whose owner is a friend. We had been whispered that our abbot is an enlightened connoisseur of his country's fine spirits. Yamada Soshō is a considerable figure: 69 years old, 56 of them in the service of Buddhism, guardian of the integrity of this "important cultural asset", he is the 27th abbot since the hermitage was founded. His role is to ensure that this place remains as his predecessor entrusted it to him, as his predecessor's predecessor entrusted it to him, and so on for over 500 years. For that's what Buddhism is all about: persistence. His title, "Jyūshoku", which is spelled「住職」from the two characters "reside" and "employment", whose job it is therefore to reside in this place, means that he is both its master and servant. He is also a strong personality. He has made his own the life of Ikkyū, that crazy, cheeky, audacious monk. He practices the irreverence of a free man.

Under his good-natured patronage, we're going to learn what "impertinence in the service of Faith"

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 6

Saaaa! Za Zen さああ〜座禅

At sunrise, it's - 4ºc. I'm expected at the Shinjū-An at 08:00 by the master of the house. I've taken the precaution of dressing warmly under my "samue": an extra layer of underwear that makes me look like a Japanese old man just out of the public bath, a sweater, a scarf, a hat, a big pair of five-fingered socks.

"Without socks, Za Zen! Next time, no hat and no scarf."

It's peremptory, but it has the merit of clarity. So we take off the socks. Toes accustomed to the cozy comfort of well-heated interiors curl up on the temple floor. A skimpy "zabuton" and its half-brother to wedge the buttocks will be the only protection.

"Za Zen is a simple principle. It's the result, "Satori", which is particularly difficult to achieve. There's no need to hang yourself up by your feet, sit on a nail-studded board or refrain from eating for 40 days. Sit cross-legged; the foot of one leg on the thigh of the other and vice-versa - I admit it's easier for a long-legged, skinny Hindu than a short-legged Japanese like me; chest straight; gaze fixed on a point in front of you; no need to hold your heart-shaped hands thumb-to-thumb, that's western sissy cinema. Just place them one on top of the other against your lap. And above all, inhale and exhale through the nose, deeply, slowly, contracting the diaphragm on the inhale, relaxing it by inflating the stomach on the exhale (I'll immediately realize that this is perfectly counterintuitive). Count from 1 to 10 per breath and then repeat, concentrating on the numbers to avoid thinking about the bills waiting for you, the dream night with your girlfriend, and what have you. This morning, we'll just do twenty minutes of Za Zen, then ten minutes of walking around the temple, and another twenty minutes."

At the end of the day, I wonder if I wouldn't have preferred to hang by my feet from one of the huge pine trees in the garden.

The torture would be more radical, the death quicker.

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 7

Journal of a temporary monk in Japan

Where there's Zen, there's pleasure!

After several hours of bitter negotiation with the Reverend, availing myself of a fragile throat and premature baldness of the vertex, I obtained for my solitary sessions to keep my cap and scarf, both matching the indigo blue "aizome" of my samue. Socks, on the other hand, were not allowed in the panoply.

Arriving at the hermitage around 7 a.m., I retrieve my zabuton from the temple's attic by climbing a staircase in name only. I place the cushion on the temple's passageway, without forgetting to salute the statue of the monk Ikkyū in the half-light of his alcove. Little by little, since that's where we have to start, I've managed to control my inhalations and exhalations. The progress is noticeable. There's no question of measuring performance, of course, but I'm down to 1.65 breaths per minute, which compares with 12 to 20 per minute for the average person at rest.

As for concentration, success is very relative. As I tick off the cycle of breaths in the approximate emptiness of my mind, it is suddenly jostled by a perfectly anachronistic thought, a truculent image, a reminder of the reality of the moment from the depths of my cortex. This cretin doesn't hesitate to remind me, even though I don't ask him to, that he's responsible for our higher cognitive functions: If it's not thought he's titillating, it's sensory perception (the breath of a zephyr), memory ("flûte, j'ai oublié encore d'acheter du pq"), language ("comment dit-on「違憲的*」en français déjà? ") or motor control (the ants and cramps in my legs). And when I proceed with the ten-minute walk down the temple passageway (157 steps, 5.6 journeys per minute, so 5.6 laps of the temple-decidedly the businessman's performance indicator reflex has a life of its own!), it's even worse: all it takes is for a cat to cross my field of vision and I have no idea where I'm at.

Bref, Satori is not for tomorrow.

*Anticonstitutionally

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 8

How those Crocs make me tense!

For the aesthete I claim to be, the famous "Crocs" worn by all the world's cooks, pastry chefs and bakers, invented by three ugly Americans who were probably tipsy when they thought them up, were the ultimate insult to the most elementary elegance. To me, they represented the height of bad taste and ugliness:

Acknowledge with me that everything about them is hideous: the shapeless shape, the air holes that randomly dot the uppers, their smell of rubber enemy of the planet and the material, a resin with filthy colors even when they claim to see life in pink, not to mention that these shoes since we have to call them that are often soiled with dirt, flour, paint, plaster, grease and other unappetizing splatters. I already had a deep aversion to the clogs of a certain doctor, supplanted by the ridiculous mules of fashionistas who emphasized the least graceful part of their feet, the heel. I had therefore strictly forbidden those Trucs, sorry, those infamous Crocs from crossing the threshold of our home.

Well, who'd have thought! Since I've been frolicking in the Shinjyū-An compound, I've never left them! They've become an indispensable accessory for the Provisional Monk that I am. They accompany me faithfully from morning to night. It has to be said that you take off your shoes, put them on again, take them off again and put them on again all day long in a temple, especially when it comes to practicing the form of "Za Zen in motion" that is the daily upkeep of the wonderful moss mats in the gardens.

Pardon me now for leaving you abruptly: my Crocs are calling me to order and to my duty, for I have two more acres of moss to pluck this morning. What do you expect, they can't do without me any more than I can do without them!

Here, then, is one of the greatest lessons I'll learn from my life at Shinjū-An:

Human nature is such that it eventually accommodates all abominations.

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 9

Recurade at the Sentõ & boiling waters 銭湯 & お湯

Recurage is the right word, but I find recurade more poetic to describe the energy the Japanese put into washing every square millimeter and every fold of their skin when they go to the Sentõ. The public bath has all but disappeared from Tokyo, but remains a lively tradition in our neighborhood.

After the last session of Za Zen as night falls, and as the sober temple bell gravely announces five o'clock in the evening, going to the Sentõ is a blessing. Under my arm a plastic tub containing soap, shampoo, shaving utensils and towels, my getas scraping the asphalt, I rush in.

The first time, I was eyed with suspicion:

Would I defile the baths by soaking in them without first washing my private parts (I've since discovered that they don't, THEY), commit the sacrilege of putting the towel I use as a sex cover (let's keep it modest) in the water (which some of THEM do quite happily), or forget to rinse off my sweat as I leave the sauna before plunging into the cool pool (I've never seen any of THEM do this)? The second time, I was made a little room in the sauna; the third, my greeting was answered with a short nod; the fourth, I was asked where I'd come from.

I expected nothing less from these proud Kyotoites who consider a business to be respectable only after two hundred years of uninterrupted presence!

I start with six minutes in the sauna, a good minute in the cold-water pool, another six minutes in the sauna, then a stop in each of the other baths, the one whose water is laden with radium (could it be from Fukushima?), the "Milky Bath" and its suspicious lactescence, the "Jet Bath" which will send your waltzes tumbling if you're not careful, and finally "The Electric Bath" whose sole function seems to me to be to electrocute with its muscle-twitching discharges any imprudent foreigner who ventures between its electrodes - I've never seen a Japanese person there!"

(To be continued!)

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 10

Ton sur Tonsure 剃髪

Well-drunken evenings are sometimes good advice. The Reverend of our Hermitage having suggested to me on leaving a bar to which he had invited me that I complete my temporary monk's outfit with a tonsure, I went the next day to the hairdresser I had spotted thanks to the uninspiring towels drying in the street.

I entered the dispensary. I spotted a surly lady in the half-light who told me to wait my turn. I was a little surprised because no one was expecting anything. I sat down on a stool while the witch disappeared into the back room. Fifteen minutes later, an old man with an uncertain stride appeared. He turned on a dusty neon sign and pointed to one of the rather slouchy skai armchairs. When I asked him for a full shave, he said: "Are you sure you won't regret it?" To which I replied that you never regret what isn't definitive; besides, there would only be one half to shave, the other being as hairy as an egg! He grabbed an antediluvian lawnmower and, in a matter of minutes, cleared away what was left of my hair. Then he brandished a menacing razor that made me regret my temerity. In Japan, you need a special license to wield a cabbage cutter. My barber in Tokyo didn't have one, so I'd never had the chance to feel the shiver that runs down your spine when the sharp steel comes to rest on your neck. My barber, despite his trembling hand, proved to be a master of dexterity: my skull and everything he shaved didn't have the slightest nick. He raved about the shape of my skull, a compliment I'd never received before. On my return, the Reverend made the same comment, adding that I resembled the Buddhist philosopher Suzuki Daisetsu, who introduced Za Zen to the West. "With the same glasses, the resemblance would be perfect," he added.

I rushed off to an optician to buy the portholes I've been wearing ever since.

Maybe one day I'll be like Suzuki Daisetsu, entitled to a mausoleum designed by a great architect?

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 11

Bath (continuation and...end?) the Goemonburo 五右衛門風呂

It took me 50 years of living in Japan to discover the Goemonburo, the "bathtub" of old-fashioned Japanese homes in the countryside. It's a metal cauldron set into a stone support, beneath which is a fireplace. A floating wooden base slightly larger in diameter than the bottom of the pot, on which you stand in a fetal position, prevents you from burning yourself on contact with the metal. All this requires a certain dexterity. If you carry your weight on one side only, you end up shaving on the lid, which applies Archimedes' principle: it rises to the surface and the soles of your feet come into contact with the burning bottom.

A friend of ours has built a goemonburo in his garden. He loves to soak in it when it rains or snows. He dons a conical pilgrim hat, sinks into the bath and sips a cold beer while his wife stokes the fire.

I attempted the adventure on a particularly cool late afternoon.

Once I'd stripped off my clothes, delighted to discover that I was well accustomed to this Kyoto cold that my Japanese friends assured me I wouldn't be able to withstand for more than a week, I cautiously slipped into this giant stewpot. I somehow managed to surf on the lid, which sank into the pot with me. Once I'd secured my balance and reassured myself that I wasn't going to leave half my epidermis stuck to the bottom of this infernal pot like a common chicken, I raised my head to the sky crowned with the tufts of bamboo and three maples that must blaze beautifully in autumn. What a state of bliss!

After a while, I noticed that the water was simmering, the first signs of boiling. In front of the fireplace, my wife was happily adding log after log, feeding a blaze that purred with pleasure in the oven.

I was about to succumb to the frog syndrome that doesn't realize it's boiling. So I jumped out of the braising pot to avoid becoming a pot au feu while my wife burst into a witch's laugh. But was it her or one of those demons the Japanese dread?

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 12

Za Zen and nature 坐禅&自然

Clearing the mind when practicing Za Zen is no easy task. There's no set method for avoiding wandering thoughts. Counting your breath from 1 to 10 sounds simple, but it only takes a brief moment of distraction to forget where you were. So it's imperative to fix your gaze on a point in front of you, if possible without blinking. In this way, you can "forget" to think. If you achieve vacuity of consciousness, strange phenomena can occur.

In my case, my body's senses take over. They perceive minute changes in the space I occupy, such as a light zephyr or the evolution of a shadow on a wall, without my brain consciously registering them and shaping a thought or reasoning such as "Here, a trickle of air!" or "The sun has moved!".

It regurgitates these sensations as thoughts once the exercise has ended.

This osmosis with nature is for me one of the tangible results of Za Zen.

It has happened, after about ten minutes of mediation, that everything around my fixation point - a root, a snag in the moss carpet, the bud on a branch - becomes completely blurred, or more surprisingly, that the environment passes into sepia or black and white and only what I fix remains in four-color. Even more surprising is the impression of "zooming" that manifests itself, as on the day when I was staring at a mandarin orange four or five meters away from me and saw it coming so close I could touch it. Interesting, too, is the wonder of the raindrops at the end of the pine needles in the garden, which I hadn't noticed and which my brain reminded me of a few hours later by formulating the following image: "Have you seen the pearls of the Shinjyū-An?". Ikkyū san had had an identical vision on a full-moon winter's night in his poor hermit's hut: noticing snowflakes falling on the floor of his dwelling, he had mistaken them for pearls, and that's how he came up with the name of the temple dedicated to his memory.

I wouldn't be so bold as to compare myself to Ikkyū san though!

Diary of a temporary monk in Japan - Note 13

At one end of the Daitoku-Ji temple compound is a tiny Shinto shrine embedded in the northern corner of the wall. It has shamelessly appropriated a square meter of Buddhist property. It's a perfect illustration of the attitude of the Japanese, who claim to be atheists but in fact accommodate any belief that comes their way according to their needs, offering no outlet for proselytizing. People are born and live Shinto, marry Catholics and enjoy a Buddhist afterlife. For my part, I maintain that their religion is called "Opportunism".

On our way to the Shinjū-An, we pass by this miniature shrine every morning and make a point of stopping for a moment to perform our devotions. For some time now, a magnificent Siamese cat has decided to become its guardian. He arrived one fine morning in January and took up residence in front of the shrine, pushing aside the vases and incense pot. There was no question in the neighborhood as to whether this pedigree animal belonged to a family sorry to have lost him. The verdict was that it was not a "Nora Neko", a stray cat, but a worthy proxy appointed by one of Shintoism's 30 million or so deities to protect the neighborhood from evil spirits. Everyone takes turns feeding him. It has to be said, though, that he's not a very nice guy. He does his job as guardian with uncompromising Japanese seriousness. When you get a little too close to the shrine's "forecourt", he gives you an icy blue stare, flicks his ears back, ruffles his beautiful champagne hair and fires away, revealing his fangs.

Nothing to do with writer Miyazaki Haruo's "Gypsy" cat, who plays a decisive role in the life of his foster family, Studios Ghibli's "Jiji" little witch Kiki or Natsume Sōseki's philosopher cat, who casts an ironic glance at his master.

And even less so with our little Chinese cat "Min-Min" who landed with us when we were living in Hong Kong. She never left us until she passed away.

class="text-align-jtify">.