Mayan writing

What is commonly known as Mayan writing is a standardized graphic system which, by means of a few hundred "word-signs" (or logograms) and around 150 phonograms marking Consonant-Vowel syllables, was used from around 400 BC until, in some regions, the end of the 17th century to transcribe several languages belonging to a linguistic family of the same denomination (Davoust 1995, Coe & Van Stone 2001, Macri & Looper 2003, Hoppan 2014). This family of Amerindian languages, which is therefore also known as Mayan, is still represented today by several million speakers in the Central American part of Mexico as well as in the two neighboring countries of Guatemala and Belize (plus a portion of western Honduras).

It was named by linguists and anthropologists after the most widely spoken of these languages, i.e. the one with the widest area of expression, corresponding to the ancient country of Yucatán (which roughly spans the three present-day Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche and Quintana Roo). Still spoken today by around a million people, this Mayan language of Yucatán is also frequently referred to today as Yucatecan, in order to differentiate it unequivocally from other languages of the same family (such as Quiché or Cakchiquel, which are spoken further south in the Guatemalan highlands), but Yucatecan speakers are the only ones who have always self-declared themselves to be Mayans, i.e. people who speak the Mayan language.

In contrast to the languages it was used to transcribe for two millennia, within a few decades of the Spanish conquest, Mayan writing was relegated to the status of something that had to be fought in the name of the Catholic faith, to be replaced by the exclusive use of the Latin alphabet, leading to a rapid loss of practice by native literates (with the exception of those in the southern and eastern regions of the Yucatecan peninsula, whose conquest was completed in 1697). Thus, Mayan writing had been a dead system (for a relatively short time, corresponding roughly to the 18th century) when, in the 19th century, a community of scholars began to emerge, keen to learn more about the still little-known history of Mayan culture. The first attempts were then made to decipher this so-called "glyphic" script, which for a long time remained very recalcitrant (Coe 1999). This quest, largely accomplished by the beginning of the 21st century (Montgomery 2002, Stone & Zender 2011), was particularly long, laborious and full of reversals.

As much for its longevity as for the quantity of documents that have come down to us (some ten thousand examples, the longest of which comprises just over 2000 signs), the Maya writing system is the one that has produced the largest corpus of (Meso)American writings from the pre-Columbian period.

Monument inscriptions

The most important category of this corpus is made up of monument inscriptions. The most representative type are those engraved on stone stelae, such as Copán's Stele 4:

.

This inscription relates, among other things, that the stele was commissioned by the 13th Mayan king of the city Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil (695-738), on the occasion of the completion of an important calendar period on August 20, 731. In a style highly characteristic of the content of monumental inscriptions from the Classical period (between the 3rd and 10th centuries), this event is paralleled by a founding event that would appear to have been the founding of the city in December 159, prior to the arrival in 427 of its 1st Mayan king Yax K'uk' Mo' (from the metropolis of Tikal, in northeastern present-day Guatemala).

Inscriptions also appear on the altars that were frequently associated with these stelae in the urban landscape of Maya cities, such as Altar Y -or Monument CPN44- which was the altar of Copán's Stela 4:

The sixteen glyphs of the inscription are distributed over the north and south sides of the monument, and allude to the birth on April 28, 563 of the paternal grandfather of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil, the 11th king (578-628) who was also the first great ruler of Copán's recent Classic period (considered to be that of the apogee of Maya culture).

While these types of documents are therefore particularly representative of what has come down to us from the great texts in classical Maya, similar inscriptions have also been discovered on other kinds of monoliths, such as ball game markers or other kinds of panels associated with monumental architecture, for example, inserted vertically into the walls of temples and palaces such as those at Palenque (in the present-day Mexican state of Chiapas), or horizontally above doorways such as the famous historiated lintels at Yaxchilán (also in Chiapas)[1]. Inscriptions even "invaded" door jambs and columns, if any, and even the risers of monumental staircases, allowing the elite to read the steps as they ascended. The most spectacular example of the latter type is undoubtedly the Grand Escalier Hiéroglyphique at Temple 26 in Copán, 21 metres high and inscribed with the longest known text from Mayan antiquity:

.

The inscription on this hieroglyphic staircase, the construction of which was initiated during the reign of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil in 710, resumed in 755 and completed in 756 by the 15th king K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil (749-761), tells the story of the dynasty founded by Yax K'uk' Mo' until the middle of the 8th century.

The glyphs of monumental Maya inscriptions were not only carved or engraved in stone, but also modelled in the lime plasters that frequently covered both interiors and exteriors[2]. However, far fewer examples have come down to us of this other type of writing and imaging support, due to the fragility of the material when exposed to prolonged humidity. In very marshy areas where the ancient Maya masons exceptionally built with baked clay bricks, as stone was difficult to obtain (as in Comalcalco, in the present-day Mexican state of Tabasco), inscriptions modelled on bricks have also come down to us. Glyphs were also painted on walls, as in the famous murals of Bonampak (Chiapas), and on cave walls (such as that of Naj Tunich in Belize).

Interestingly, we should also mention the existence of graffiti. This particularity is interpreted, in the context of ancient civilizations in general, as a sign of a certain form of democratization of writing. However, rather than truly expressing popular speech, Mayan graffiti seem to tend to imitate the academic models of monuments[3].

Inscriptions on furniture

A roughly comparable number of epigraphic inscriptions, albeit shorter overall, also exist on movable media. Ceramics are the most abundant type, and dating of this type of source is again essentially from the classical period (Coe 1973). As on monuments, glyphs are engraved, incised, modelled or painted, as on "Vase K1523"[4], whose inscription indicates that it was the drinking cup of "fruité de cacao" for a member of the elite of the great kingdom of Kaan[5]:

.

Mayan ceramics bearing glyphic inscriptions are mainly vessels, in particular cylindrical vases and dishes, but there are also figurines bearing such inscriptions, and numerous small texts on movable supports exist in addition on polished and engraved stone artifacts -in particular fine stone jewelry pieces, such as jade- but also on various bone or shell objects. Finally, for epigraphy, we should mention various kinds of hard supports of intermediate types, such as thrones, statues, sarcophagi, "double spiritual receptacles" or waybil (which in Copán were given the form of scale models of houses....)

Although dedicatory inscriptions are not absent on monuments (which are the main medium of dynastic propaganda of the type evoked with the Copán example, see Schele & Freidel 1990, Martin & Grube 2000), they are mainly the result of furniture, such as the "K1523 Vase", but ceramics also bear numerous "iconographic legends" whose function was to comment on the mythological representations painted or engraved on these valuable objects (Coe & Kerr 1998)[6].

These different types of epigraphic sources are therefore what have come down to us from the heyday of Maya culture (which is in particular the so-called Late Classic period, between the 6th and 9th centuries), due to the fact that they are the most perennial media that have best resisted the damage of time and the humid heat prevailing in most of the Maya zone. Indeed, from the early Classical period onwards, numerous "illuminated" manuscripts with texts painted in black ink on Mesoamerican paper[7] were widely used by the literate elite, and there is ample evidence to suggest that paper was the most common medium for Maya writing from this period onwards.

Inscriptions on paper

Manuscripts were made up of a long strip of paper, obtained by assembling numerous sheets - some twenty centimetres high and around ten centimetres wide - side by side. The whole thing was folded on one side and then on the other, like a small folding screen. The fragility of their support in the climate of the Maya zone - given that the heat and ambient humidity in most of these regions (located entirely between the Tropic of Cancer and the Equator) are not conducive to the conservation of paper - but also the destruction of anthropic origin (in particular the auto-da-fés ordered from the 16th century onwards by the Spanish inquisitors) meant that the vast majority of them disappeared.

Only three, perhaps four, survived. The three copies whose authenticity is unanimously accepted are preserved in the European Union: the Dresden Codex, the Paris Codex and the Madrid Codex. All three were in use at the time of the Spanish conquest and were sent to Europe relatively early on, hence their preservation. Published in facsimile form in New York in 1973 and now preserved in Mexico City, a fragment of a fourth Maya codex may exist: the Grolier Codex (Coe 1973)[8]. That said, the very dating and authenticity of this document are controversial, and its contents consist not of genuine glyphic texts but of a series of pure date tables combined with imagery reminiscent of the "Venus almanac" of the Dresden Codex.

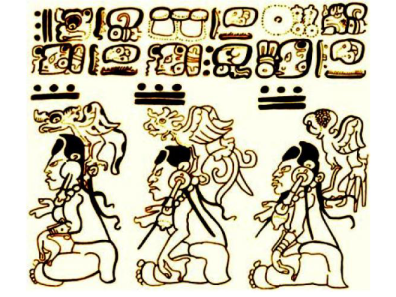

The contents of these rare Maya codexes to have come down to us are of a similar kind. They are collections of divinatory almanacs, with astrological and/or prophetic content, suggesting that these manuscripts were essentially manuals for diviners. Of variable length, the sections or "chapters" that make up each of these almanacs are generally painted on one of the three horizontal registers that usually divide each page, and this, on one or more consecutive pages.

Each almanac represents a period of time and is divided into a greater or lesser number of compartments, each representing a temporal sequence placed under the sign of a divinity and associated with an omen. The latter is generally noted in a short, simple manner, in a double column of four to six glyphs each, and the presiding deity(ies) is/are represented in a vignette below the inscription, while, from an initial date table, figures indicate the length of travel required to move from each sequence to the next (as well as the date reached):

.

Almost 3.5 m long when unfolded, the Dresden Codex has 39 leaves measuring 20.5 x 8.5 cm, totalling 78 pages, 4 of which are blank on the reverse (Davoust 1997). This codex dates from the recent post-classical phase, pre-dating contact (probably from the very beginnings of this phase, in the 14th century). It was purchased in 1739 by the Saxon Library in Dresden. In addition to being considered one of the most classical and beautiful, the originality of this manuscript lies in the fact that it contains the most complex almanacs, where the link with astronomy is most obvious.

A remnant of the first eleven leaves of a manuscript approximately 1.4 m long, but which originally included at least four more pages (i.e. a total of at least 26, initially), the Paris Codex in its current state comprises 22 pages, each measuring 23.5 x 12.5 cm (Love 1994). This badly deteriorated codex dates from the same period as the Dresden codex, but is slightly later (possibly mid-15th century). It is currently housed in the Mexican Collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, and the main originality of this manuscript lies in its almost complete "almanach des katun", establishing prognoses for a cycle of [13] periods of twenty years of reckoning (of 360 days, or 7,200 days). This document appears to be the most comparable to the prophetic literature in the Yucatecan language and Latin characters of the colonial era, in the so-called Chilam Balam books.

Probably incomplete, the Madrid Codex currently consists of the union of a fragment known as Codex Troanus, approximately 2.6 m long and comprising 21 leaves (i.e. 42 pages, each measuring 23 x 12.4 cm) with a fragment known as Codex Cortesianus, approximately 4.4 m long and comprising 35 leaves (i.e. 70 pages, of course in the same format as the other fragment). What remains of the whole thus exceeds 7 m in length and comprises 56 leaves, or 112 pages. The dating of this codex is even more controversial. While it is accepted that it is the latest of the three, some scholars believe it may date from the 15th century, while others date it from the 17th century. The controversy is due in particular to the presence, in the traditional Mesoamerican paper support, of fragments of European paper bearing annotations in Spanish. According to the latter, these fragments were embedded in the Mesoamerican paper when it was being prepared, suggesting that the codex was not produced until the 16th century (or even the 17th), probably in a region of the southern Yucatán peninsula that had remained untouched by the Spanish until then, but this observation is disputed.

The "little great treasure" represented by Maya glyphic writings of the paleographic type appears to be a vestige as small as it is peculiar and out of step in both genre and time. Several centuries after a profusion of epigraphic sources with an entirely different content, it comes belatedly to give us a glimpse - at a time when monuments and ceramics, even ceremonial ones, had become practically mute - of a type of divinatory practice whose origins and development before the Postclassic period are difficult to reconstruct precisely. For Mayanists, these precious codices have become a curious link between the mythico-historical "sagas" of classical epigraphy and the Mayan literature of the colonial period in Latin characters (Álvarez 1974).

It should be stressed, however, that while no other type of manuscript apart from the three soothsayer manuals from Dresden, Paris and Madrid has come down to us, indirect evidence points to the existence of many other genres, for example manuscripts with historical and mythological content, as well as probably administrative documents, such as the tax registers inherent in state societies. But none of these documents has survived the centuries, still less the drafts and school exercises that the existence of writing might also suggest, nor any writings that might have dealt with everyday life, if indeed this all-encompassing material ever existed among the ancient Maya.

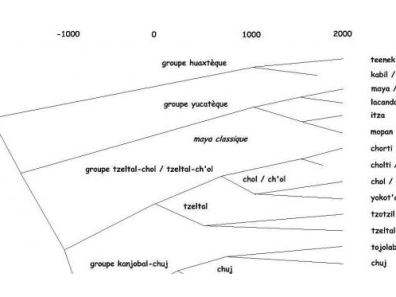

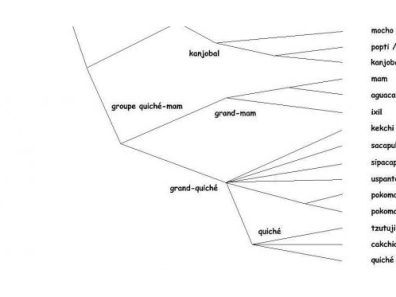

The deciphering of what has come down to us in such an uneven fashion suggests that Mayan writing appeared at the beginning of the recent pre-Classical period in the highlands of present-day Guatemala and the lowlands of the peninsula (towards the present-day Guatemalan department of Petén), in order to transcribe the language of an elite speaking an eastern dialect of the "tzeltal- chol" branch of the Mayan languages (of which the Mayan language was one of the most important).chol" branch of the Mayan languages (the most direct heir of which would be the present-day Chorti of eastern Guatemala). Then, in the 3rd century, this script took on its so-called "Classic Mayan" form and was adapted in the centuries that followed (in the Early Classic period, between the 3rd and 6th centuries) to transcribe also the western dialects of the "Cholan" branch of the ancient "Tzeltal-Chol" branch (whose most direct heirs are Chol from Chiapas and Chontal from Tabasco), then in the Late Classic for Tzeltal, Yucatecan and - very exceptionally - for some highland languages such as Ixil and Quiché. Finally, the form adapted to Yucatecan is the one that, from the end of the Classical period onwards, gave rise to what we find in the rare manuscripts that have come down to us, although numerous "fixed" spellings of Cholan origin can still be found in the Dresden, Paris and Madrid codices (Lacadena 1997, Macri & Vail 2009).

Jean-Michel Hoppan

Ingénieur d'études, CNRS, UMR SeDyL

L'UMR SeDyL (Structure et Dynamique des Langues) is a language science laboratory with three tutelles: CNRS (UMR 8202), INALCO, and IRD (UR 135).

http://www.inalco.fr/recherche/sedyl

References

Álvarez, María Cristina. 1974. Textos coloniales del libro de Chilam Balam de Chumayel y textos glíficos del Códice de Dresden. Cuaderno 10. Mexico: Centro de Estudios Mayas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Coe, Michael D. 1973. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: The Grolier Club.

Coe, Michael D. 1999. Breaking the Maya Code, Revised Edition. London (and New York): Thames and Hudson.

Coe, Michael D. & Kerr, Justin. 1998. The Art of the Maya Scribe. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Coe, Michael D. & Van Stone, Marc. 2001. Reading the Maya Glyphs. London (and New York): Thames and Hudson.

Davoust, Michel. 1995. L'écriture Maya et son déchiffrement. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Davoust, Michel. 1997. A new commentary on the Dresden Codex. Fourteenth-century Maya hieroglyphic codex. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Hoppan, Jean-Michel. 2014. Let's talk classic Maya. Deciphering glyphic writing (Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras). Paris: L'Harmattan.

Lacadena, Alfonso. 1997 Bilingüísmo en el Códice de Madrid. Los investigadores de la cultura maya, 5, pp. 184-204. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche.

Love, Bruce. 1994. The Paris Codex: Handbook for a Maya Priest. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Macri, Martha J. & Looper, Matthew G. 2003. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs,Vol. 1, The Classic Period Inscriptions. Norman: University of

Oklahoma Press.

Macri, Martha J. & Vail, Gabrielle. 2009. The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs,Vol. 2, The Codical Texts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Martin, Simon & Grube, Nikolai. 2000. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya, London: Thames and Hudson.

Montgomery, John. 2002a. Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Montgomery, John. 2002b. How to read Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Schele, Linda & Freidel, David. 1990. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya, New York: William Morrow and Co, Inc.

Stone, Andrea & Zender, Marc U. 2011. Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. London (and New York): Thames and Hudson.

Notes

[1] A few specimens of lintels made of almost rot-proof sapodilla wood have also come down to us, notably at Tikal.

[2] Somewhat abusively, this type of plaster is commonly referred to in Mayan archaeology by the generic term "stucco".

[3] That said, the well attested use of date glyphs, even in the most rudimentary of these graffiti, suggests that even subjects without the benefit of a literary culture were at least familiar with this type of notation.

[4] This denomination means that the photographic scroll of the object is recorded under number 1523, in J. Kerr's corpus of Maya mobile artifacts: http://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya.html.

[5] In the central lowlands of the Yucatecan peninsula, the kingdom of Kaan was the great enemy of that of Tikal. Its main capital was the city of the "three stones" Oxtetuun, now the archaeological site of Calakmul (in southeastern Campeche).

[6] These sequences of glyphs, generally shorter than the dedicatory formulas, sometimes act as phylacteries, as in the speech bubbles of a comic strip.

[7] Known as amate (a term borrowed from the Nahuatl amatl "ficus", "paper", "written (on paper)"), "Mesoamerican paper" is a type of medium obtained by beating the liber - i.e. the inner bark - of local varieties of fig trees (trees of the ficus genus). The surface was smoothed and whitened by applying a lime coating, which then received the pictorial layer. Although some populations - such as the Mixtecs of the present-day Mexican state of Oaxaca - preferred to use a type of parchment (made from the skins of animals such as local deer), amate was used in pre-Hispanic times by various peoples of Mesoamerica to make their books. In Mayan, its name is juun, which - like its Nahuatl equivalent amatl - designates both trees of the ficus genus, the paper made from them and the written documents that use it as a support.

[8] On the basis of the circumstances of its discovery, the manufacture of its support (as atypical as that of the pictorial layer), its imagery as clumsy as it is little in keeping with the usual Maya canons, but also because the age of the paper is no proof of that of what was painted on it, this manuscript -which is the only Maya codex not to have been anciently recognized- remains considered by some researchers to be a forgery. Among those who believe it to be true, some claim that it is even the oldest known Mayan codex - carbon-14 dating of a sample of its support having given a range of 130 years around 1230 - while others believe that it is more likely to date from the early colonial period and would therefore be the most recent.