Aztec diviners writing the weather

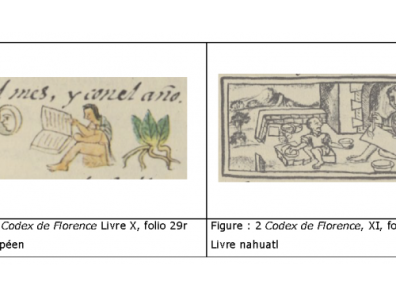

In this field, Father Bernardino de Sahagún stands out. This Franciscan, who was born in Spain but arrived in Mexico at a young age, soon had the idea for a remarkable work. To write a book dealing with all aspects of Aztec civilization, interviewing the Aztecs themselves and including in the projected book on the one hand their testimonies, in the Nahuatl language in Latin characters, alongside his own translation and adding vignettes which, unbeknownst to him, recovered certain elements of Aztec pictographic writing. This work is fundamental: on most subjects, it provides either information that exists nowhere else, or details that cannot be found in other sources.

The calendar according to Sahagún

Sahagún conceived his work, which today bears the title of Codex of Florence, for the simple reason that this manuscript is preserved today by the library of this city, in twelve books. It so happens that he devoted an entire book, the fourth, to the theme of divination, and he begins the book as follows: "De l'astrologie judiciaire ou de l'art de la divination que ces mexicains utilisaient pour savoir quels étaient les jours chanceux et ceux malchanceux et quelles conditions auraient ceux qui naissaient les jours attribués aux caractères ou signes qui se mettent ici et qui semblent relever de la nécromancie et non de l'astrologie. Chapter I, of the first sign, called ce cipactli, and of the good fortune that those born on that day, whether male or female, would have if they did not lose it through negligence or laziness. Thus begin the characters for each of the days they counted by thirteen. There were thirteen days in each week, and they made a circle of two hundred and sixty days and then started again at the beginning[1]."

This introduction mentions a fundamental fact namely that divination was done with the help of a "circulo".

This introduction mentions a fundamental fact, namely that divination was carried out using a "circulo", a "circle" which he is reluctant to call a calendar, for the simple reason that the circle closes after 260 days, not 365.

The days

Sahagún also informs us that this cycle "comprises twenty signs multiplied by thirteen[2]", here he is referring to the names of the days, which have the particularity of being composed of two parts: the first is numerical, it's a number between 1 and 13, the second is lexical it's a noun from the Nahuatl language.

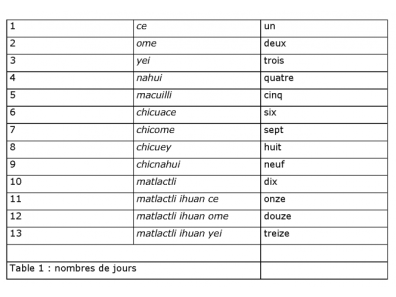

The numbers are called:

The words for days come from the animal world, flora, natural phenomena and a few artifacts.

They are as follows:

The combination of the numerical part and the lexical part gives the following sequence:

This 260-day cycle, called tonalpohualli, repeats itself ad infinitum, and only every 260 days (13x20) will a day bear the same name.

Where do the numbers 13 and 20 and their combination come from?

The number 20, the sum of a man's fingers, corresponds to the basis of the vigesimal system in force in Mesoamerica. The number 13, on the other hand, is far more mysterious. There are only a few hypotheses as to the product of the two numbers. Among the hypotheses put forward, three are the most interesting: it would correspond, roughly speaking, to the gestation period of a woman[4]; it would correspond, roughly speaking, to the periods of visibility of Venus; finally, it could be a purely mathematical/astronomical choice to align the various calendars with the natural movements of three stars (Sun, Pleiades, Venus).

The invention of the tonalpohualli, based therefore on the product of 13 by 20, is attributed to a couple named Cipactonal and Oxomoco, but also sometimes to Quetzalcoatl.[5]

This combination of a number and a name bears the Nahuatl name, language of the Aztecs, of tonalli. This word is analyzed as tona-l-li i.e. we have a verbal root followed by a nominalizing suffix and finally an absolute suffix. The verb tona means "to make hot, to make sun, to shine (speaking of the sun)". In the literal sense, it's "that which is resplendent, that which is warm". In dictionaries we'll find for the word tonalli the meanings of "heat of the sun", "sun", "summer, dry season" and also "day", understood as a period of twenty-four hours. And in the possessed form, itonal or tetonal, we find in addition the meaning of "soul, sign" which Alexis Wimmer renders as "the calendar sign under which someone is born and which determines their destiny"[6].

Tonalli is not the only word to mean "day". The word ilhuitl can be translated in the same way. However, the usage of the two words is not identical, showing that they are not really synonyms. A fundamental difference lies in the fact that to express a certain number of days it is always ilhuitl that will be used and never tonalli. On the other hand, the word ilhuitl can appear in the form cemilhuitl. All words beginning in this way with cem- or cen- are units of measurement. This fact added to the fact that only ilhuitl is pluralizable shows that the common translation as "day" conceals a fundamental fact. Namely that ilhuitl designates only time, and for this reason it can be added together, whereas tonalli cannot be dissociated from the forces, influences, powers it expresses. An tonalli is a day with all its particular potentialities, while an ilhuitl is only time[7]. A tonalli, because of its name formed of a number and a word, can only be unique in principle. A tonalli is a day seen in its qualitative aspect, while ilhuitl is its quantitative side.

On the basis of tonalli the Nahuatl constructed the word tonalpohualli which is used to designate this period of 260 days[8]. Tonalpohualli is analyzed as tonal-pohua-l-li i.e. a nominal root, tonalli "day, spell", a verbal root pohua "count, read, tell" and the nominalizing suffix -l followed by the absolute suffix -li. Two other important words were built on this word tonalli, these are tonalamatl and tonalpouhqui. Tonal-ama-tl is composed of two nominal roots, the second of which, amatl means "paper, book", so the tonalamatl is "the book of days, of spells". Tonalpouhqui is an agent name formed on tonalpohua, meaning "the reader, storyteller and counter of days, signs, fates".

The value of the days

Reading this Book IV, which follows the order of the 260 days of the divinatory calendar, brings home a number of facts:

Each day is considered in three modes: it can be good, bad or indifferent.

At least, that's how Sahagún writes it. In fact, for those who wrote the Nahuatl text, which the Franciscan translates more or less freely, there are not three terms but only one that defines a sign. It is either cualli "good", or amo cualli "not good", or finally cualli ihuan amo cualli "good and not good"[9]

A good sign is one that gives hope of prosperity and a long life, a bad sign will determine a dissolute and poor life, as for example that of the drunkard.

The beneficial nature of a sign is not enough to ensure a good life. It is also necessary to conform to the content of the sign itself. Thus it is said that a woman born on a day 1 xochitl that she will be a good seamstress, "it was necessary, in order to enjoy this skill, that she be very devoted to her sign and do penance every day it reigned[10]". We understand that those born on a certain day had to worship the deities who patronized that day. One could also lose the beneficial character of one's sign through negligence or laziness (Sahagún, 1989, p. 233)

The day of birth was particularly important, as it determined the auspices under which life would unfold. However, the determination was not mechanical, as the tonalpouhqui had the power to shift, as it were, this date, and this within a limit of four days.

In the Sahagún text the beneficial or malefic character of a sign applies with different modalities according to sex, social class (noble or common man), professional category (craftsman, tradesman...). There is an analogical relationship between certain signs, Mazatl and Itzcuintli, and the character of those born under them. (Sahagún, 1989, p. 237; 241)

Sahagún places great importance on numbers. In many cases, they determine whether a day is beneficial or not. Thus, he often describes only the first sign of the thirteen and goes on to simply list the following signs and say "these signs follow the good or bad character of their numbers" (Sahagún, 1989, p. 263). Numbers 3, 7, 10, 11, 13 were good, while 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12 were bad. Sahagún's tendency is to associate goodness with odd numbers and badness with even numbers. The same idea is found in another Franciscan, Motolinía[11]. On this point, the two brothers diverge from another Dominican friar, Diego Durán. The latter emphasizes names rather than numbers in determining the character of a sign[12].

Comparison[13] between the two authors, Sahagún and Durán, reveals that in 11 cases the two authors agree, in 4 cases they totally disagree, and in the remaining 5 cases the disagreement is less clear-cut.

Sahagún emphasizes the use of the divinatory calendar in connection with birth and the imposition of the name[14], but this was not its only use[15].

With the conquest the Aztecs discovered the European conception of almanacs, particularly those used for cultivation. How were these calendars received? The Nahuatl language tells us: they were kept separate and distinct from the tonalpohualli and its usages. New words were forged to cope with this new reality: neologisms such as amoxmatini "book connoisseur", tonalpoani"day counter", metztlapoani "moon counter" and xippoani "year counter" were created[16] to speak of gardeners. These words are not used for any other characters[17] and were forged specifically for European use in books specializing in horticulture, i.e. almanacs. This is confirmed by the vignette corresponding to this text, which shows a European book quite distinct from a native codex. Sahagún's informants avoided using the usual words to show that this practice was completely foreign to them.

Sahagún's idea of the tonalpohualli is expressed not only in his text but also, and perhaps even more obviously in the three plates that accompany this Book IV of the Codex of Florence:

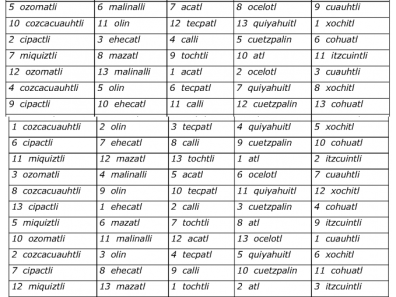

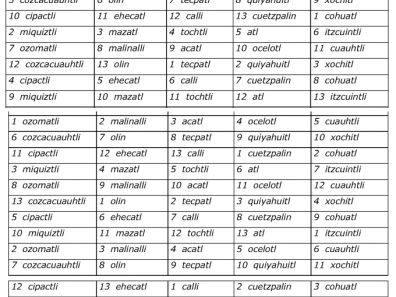

Everything here is reduced to an ordering of numbers, with the 20 glyphs of the days in the first column on the left and then the 13 columns induced by this presentation, with in each box the number corresponding to the place of the days.

In doing so, Sahagún all at once misses (voluntarily or involuntarily) the main content of these divinatory calendars and at the same time captures an essential aspect, of the knowledge of the tonalpouhque. By creating a table with 2 entries, 20 X 13, he simply reiterates, but in a gaunt way, a fundamental knowledge of tonalpohualli specialists. A cycle of 260 units is divisible by several numbers (65, 52, 20, 13, 10, 5, 4...) and this property can be used to create multiple arrays. And the tlacuiloque, "painter-writers", masterfully exploited this property and thus offered those entrusted with reading and interpreting them documents of great complexity and richness as regards divination.

As noted by Eloïse Quiñones (2004, p. 133), the gods were almost completely excluded from this divinatory calendar; they seemed to play no role at all. "It is the final fate of the day and its effects on individuals that constitute the heart of the text. Natural forces are also eliminated: no deities are mentioned, nor are any of the mantic forces. And yet it was these forces, on a par with day signs, that were the very essence of the painted images of the tonalamatl. Finally is also eliminated any sense of the ritual process by which the pre-Hispanic diviner read these images in order to obtain a final prognosis and define the actions to be taken."

It turns out that understanding the calendar cannot be reduced to its mathematical workings, nor can its divinatory function be reduced to the powers attributed to numbers.

The gods in Sahagún

The Sahagún text, which in this respect follows the original Nahuatl version very closely, is not totally devoid of allusions to deities. Of the 260 days mentioned, there are only thirteen allusions to gods, which can be divided into two groups. The first (6) concerns the first days of the thirteen weeks, and thus seems to refer to the patron deity, and the second (7) mentions deities in relation to specific days.

In these allusions, what Sahagún translates as reinar "to reign" is most often expressed in Nahuatl by a verb with a significantly different meaning. This is the verb tonaltia, derived from the noun tonalli, which in its transitive form with an animate object prefix te- means "to dedicate, to celebrate [18]". Reinar can also be rendered by the verb tlatoa "to speak" either simply in this form or in the derived word itlatoaia (i-tlato-yan) which means "his moment to speak" or by the verb tlatalhuia formed from the verb italhuia which means "to speak of someone" [19].

So of day 9 Acatl it is said that he was unlucky because on that day "reigned the goddess Venus whom they called Tlazolteotl"[20], while the Nahuatl text says: Auh in chicunavi acatl : çan njman amo qualli, ipampa qujlmach itlatoaia, itlacemjlhujtiltiaian Tlaçolteutl, (CF,IV, 74)

Nahuatl does not speak of "reigning" but indicates that the day was not good because it was "his time to speak" i-tlatoa-yan, it is "his period of a day" i-tla-cem-ilhui-ti-ltia-yan of Tlazolteotl.

There are therefore only six gods as regents of the thirteen weeks, out of a possible twenty, that Sahagún mentions, while he indicates the influence of a deity on a particular day in only 7 cases out of 260! Moreover, with the exception of Tezcatlipoca in 1 Miquiztli and probably Tonatiuh in 1 Tecpatl, none of the deities cited by Sahagún correspond to what we know from the tonalamatl.

To try to understand how Aztec diviners used the tonalamatl it is necessary to try to reconstruct the data set that codex reading specialists, the tonalpouhque, had to take into account in order to be able to tell their consultants what the signs were saying? As E. Quiñones "the mediation of the diviner was crucial in the divination process. The tonalamatl did not contain a list of well-defined omens like the modern astrology books that any curious reader can peruse. Only the mantic ingredients were painted in the divinatory manual, and these had to be weighed up carefully to arrive at a final interpretation[21]."

The tonalpohualli in twenty thirteen-week periods

Sahagún mentions that the tonalpohualli was organized in twenty thirteen-day periods, and he gives two schematic versions. The first (see Figure 3) is organized in the form of a table with the twenty days on the ordinate and the thirteen numbers on the abscissa[22]:

While the second reproduces a continuous sequence of the tonalpohualli, i.e. indicating for each of the 260 days, in order, its glyph and number. This second version is organized as a table with the twenty days on the abscissa and the thirteen numbers on the ordinate. Each line corresponds to a thirteen-day period, and the 20 are distributed by 10 on 2 pages of the Codex of Florence.

These two ways of representing the calendar provide no information for divinatory use. If we assume that the information given by Sahagún is complete, i.e. that the beneficial or non-beneficial nature of a day would be based entirely on the value of the number, such tables would be perfectly useless. It would have been enough to know the value of the numbers, and no written support would have been necessary. This sanitized presentation does not correspond to any of the known tonalamatl indigenous.

This type of organization, in twenty thirteen, can on the other hand be observed in six codices named: Borgia, Vaticanus B, Telleriano-Remensis, Vaticanus A, Borbonicus and Aubin.

Examining each of these examples and reconciling them with all the information at our disposal gradually enables us to perceive the multiplicity of divine influences to which the days were subject, either individually or as part of a period.

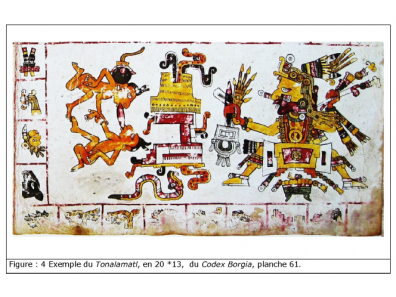

Tonalamatl Borgia

Each of the twenty treizaines of this tonalamatl, one of the only ones unanimously considered to predate the Conquest, is organized as follows:

In the center are the principal and secondary deities and ritual objects. At the periphery are the names of the days, expressed only by their lexical part, the numbers not being expressly indicated.

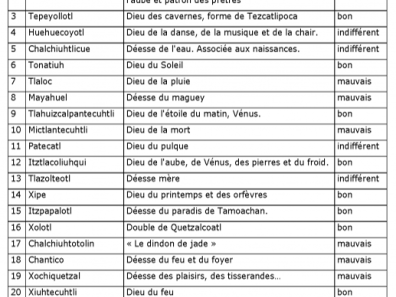

The principal deities, each of which governs a thirteen-week period, are substantially identical in all the tonalamatl ordered by 20 x13.

If we take into account the indications given by Sahagún about the overall favorable or unfavorable character of each of the thirteen-week periods, and assume that this "color" was given by the principal deity of that period, we can then attribute to each of them the following character:

A similar structure is found in another codex, close to the Borgia, the Vaticanus B.

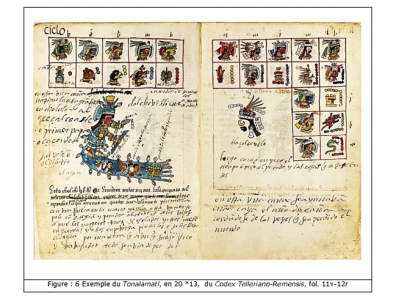

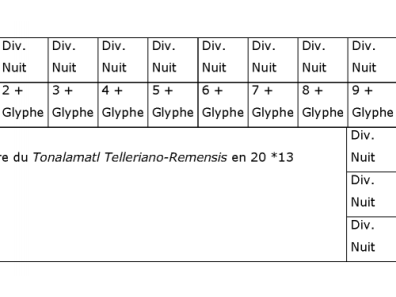

Tonalamatl Telleriano-Remensis - Example of the Tonalamatl, in 20 *13, from the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, fol. 11v-12r

In the Telleriano-Remensis, a codex produced after the conquest at the instigation of religious figures, the ordering is a little more complex. Still surrounding the main and secondary divinities are the thirteen names of days expressed by the association of a glyph and a number. Parallel to the names of the days is a series of nine deities, traditionally called the Lords of the Night or the Nine Lords, which are thus repeated throughout the Tonalamatl. 9 not being a divisor of 260 the last day of the tonalpohualli represents two deities instead of one[23].

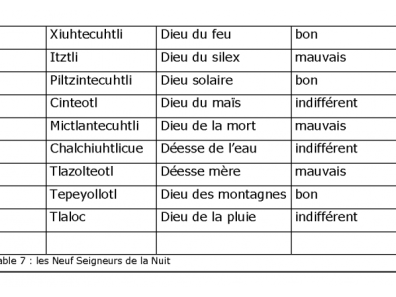

The Nine Lords of the Night are as follows:

Thanks to the annotations on the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, indicating the beneficial nature of these Lords of the Night, as well as the associated images in the Codex Borgia, their divinatory value is known and can therefore be associated with them[24].

Tonalamatl Vaticanus A

Another Tonalpohualli, that of the Codex Vaticanus A has exactly the same structure as that of the Telleriano-Remensis.

Tonalamatl Borbonicus

In this tonalpohualli we find the day glyphs, the accompanying numbers and the Lords of the Night. Added to this are two new additions: the Day deities and the Volatiles. Both are 13 in number and accompany each day of the thirteen-day period.

The thirteen deities who accompany the days are more or less the same as those who rule the thirteen weeks.

The only newcomers are Tlaltecuhtli "god of the earth", Yohualtecuhtli "god of the night" and Citlalinicue "goddess of the starry sky". Their precise role and divinatory value are unknown. Hypothetically, I have attributed to these divinities the same connotation as theirs as regent of a thirteenth or sometimes as deity of the Night. In the absence of any information, I have assigned them the status of indifferent.

The Volatiles are associated in the Codex Borgia with numbers[25] so they were assigned the same divinatory values as the numbers, i.e. Motolinía's information that odd-numbered days are good while even-numbered days are bad was followed.

![Aztèque - Structure du Tonalamatl Aubin[26] en 20 *13.](https://inalco.fr/sites/default/files/styles/4x3_sm/public/2024-07/bk_table_suite_code_14.png?h=484d87de&itok=pkUkugHX)

Although the layout is different from that of other documents, the components are largely the same. Namely, the glyph for the name of the day, its number (between 1 and 13), the succession of the nine nocturnal deities, the thirteen deities of the Day and the Volatiles. But here, unlike the Tonalamatl of the Borbonicus, the Night deities are dissociated from the name of the day and occupy a column of their own. On the other hand, the 13 gods of the Day are also dissociated from the Volatiles and form a new column of their own. Finally, the last column, closest to the central scene, houses the Volatiles and a new series of 13 deities, deities that appear only in this document[27].

We have no information as to the role of these new thirteen deities, so no values have been assigned to them.

Values of numbers, glyphs, deities

All the sources used showed that each day was subject to influences through :

- its number (Sahagún, Motolinía)

- its name (Durán)

- the main deity of the thirteenth (Sahagún)

- the 9 deities of the Night (Telleriano-Remensis, Tudela)

- the 13 deities of the Day

- the 13 Volatiles

- the 13 deities associated with the Volatiles

Divinatory values are attested for numbers, names and the main deity. On this basis it is assumed that the other deities or Volatiles that appear in the Tonalamatl play a similar role and are capable of influencing either for good or ill the quality of a day.

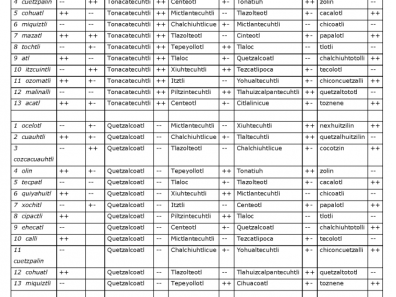

If we apply the three possibilities encountered -good, indifferent, bad-, to the Tonalamatl of the Codex Borbonicus, for example, we can draw the following table, where ++ indicates a favorable influence, -- an unfavorable influence and +- marks indifference:

Applying the values to the Tonalamatl Borbonicus

This schematic presentation of the beginning of the Tonalamatl from the Codex Borbonicus gives an idea of the complexity of the data that had to be taken into account by the tonalpouhque, the readers of the tonalpohualli, before they could decide on the nature of a day and whether or not it was beneficial. Of course, we don't know what weight each of these data might have carried. Nothing tells us that the power of a god of the night was identical to that of the regent of the thirteenth or the regent of the day. For the sake of convenience, we assume that they all have the same importance, but this is obviously just an artifice.

The other provisions of the tonalpohualli

The division of the tonalpohualli into 20 periods of 13 days each is just one way of organizing the days. Authors such as E. Seler and then A. Nowotny, in particular, have shown that the tlacuiloque "writer-painters" systematically exploited all the possibilities offered by the fact that 260 is a multiple of 65, 52, 26, 20, 13, 10, 5, 4 and 2. They used paintings, varying the number of rows and columns as it were, to take advantage of these mathematical features.

Three examples, taken from the Codex Borgia, will enable us to appreciate how the "writer-painters" were able to play jointly with three factors: the subtle simplicity of mathematical relationships, the synthetic power of paintings and the extreme richness of images.

Codex Borgia, Plate 72

Figured on this board is a tonalpohualli in 4 x 5 x 13. This plate is divided into four parts, each under the dominion of a deity. Starting from bottom left and turning counter-clockwise we find: Tlaloc, Tlazolteotl, Quetzalcoatl and Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl. Related to the body of each are the 20 day glyphs. Five for each: Cipactli, Acatl, Coatl, Olin, Atl associated with Tlaloc; Ocelotl, Miquiztli, Tecpatl, Itzcuintli, Ehecatl associated with Tlazolteotl; Mazatl, Quiyahuitl, Ozomatli, Calli, Cuauhtli associated with Quetzalcoatl and finally: Xochitl, Malinalli, Cuetzpalin, Cozcacuauhtli and Tochtli associated with Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl.

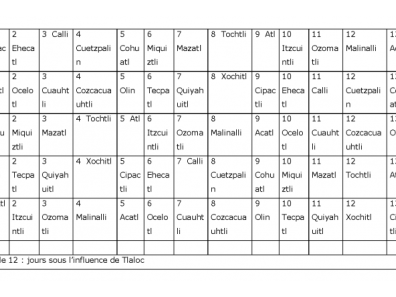

Each quarter is delineated by a snake featuring 12 circles. These circles indicate that each of the five days and the following twelve are under the domination of the deity on which they depend. Thus, in the first quarter, 5 x 13 = 65 days are affected by Tlaloc's powers:

.

The same applies to the other quarters and these influences are, no doubt, superimposed on those of the other 13-day periods, such as those of the tonalpohualli in 20 x 13.

Codex Borgia, Plate 56.

This plate features a tonalpohualli arranged in 10 x 2 x 13. On each side of the image are ten day names, i.e. counting the two columns, the totality of day names. Between these two columns are twelve red dots at the top and bottom. It's these 12 dots, combined with each sign, that allow you to move from 13 to 13. Thus the thirteen beginning with Cipactli, Mazatl, Acatl, Quiyahuitl, Cohuatl, Ozomatli, Olin, Calli, Atl, Cuauhtli are under the influence of the god Quetzalcoatl (the deity to the right of the central image), while all the other ten thirteen are under the dominion of Mictlantecuhtli. The odd-numbered thirteen are under the influence of the god of Wind, while the even-numbered ones are under that of the god of Death[28].

So in the first example one day 5 Cohuatl was under the dominion of Tlaloc and with this new arrangement that same day finds itself ruled by Quetzalcoatl. Because of the different divine arrangements and attributions, each day can thus be subject to a very large number of influences.

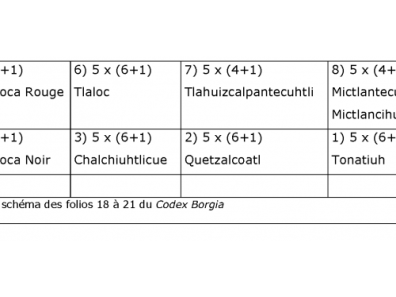

Codex Borgia, Plate 18 - 5 x (6+1)

.

This plate is part of a set of 4 plates that are all graphically structured in the same way: two registers each comprising a series of five day names. Each register contains a number of units, red circles, which act as multipliers. In order, we find the numbers: 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 4 and 4, to which must be added a unit given by the day. The whole tonalpohualli, i.e. the 260 days, is expressed as follows:

Tonatiuh, the sun god, thus governs the days Cipactli and the following six, as well as the days Acatl and the following six, Coatl and the following six, Olin and the following six and finally Atl and the following six. And so on for the eight divisions of the tonalpohualli.

Displayed in the form of two-entry tables (20 columns and 13 rows), by coloring the periods we obtain the following layout of the tonalpohualli. Knowing that each color corresponds in the Codex Borgia to one or two deities who exercise their powers over the days of that same color, we can imagine the complexity of the system and understand that it was essential to call on specialists to know which days were favorable or not. Today, computers make it possible to reproduce the "mechanical" part of the process.

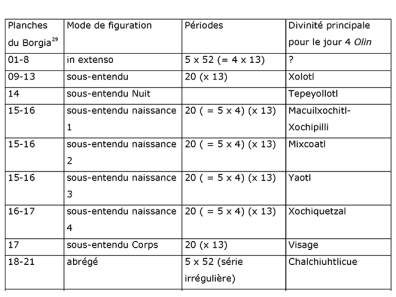

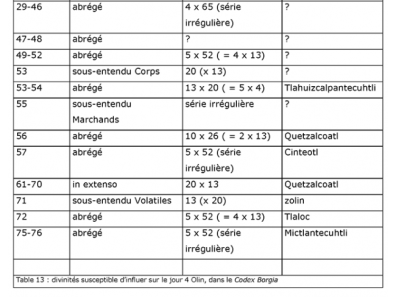

Suppose we want to know the influences on day 4 Olin, the seventeenth day of the tonalpohualli, the three previous examples allow us to say that this day is under the influence of Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl and Chalchiuhtlicue. But if we consider all the presentations of tonalpohualli in the Codex Borgia we find that day 4 Olin is under the domination of all the deities cited in the following table:

Each day can belong to a period of 65, 52, 26, 20, 13, 10, 5, 4 or 2 days, and each of these periods is subject to a particular god.

Thus any one day can be under the dependence of as many gods as there are divisions of the tonalpohualli, i.e. more than a dozen. This figure corresponds to the divisors of 260, but to this should be added cases of unequal divisions, such as those seen in the last example of the Codex Borgia.

The following diagram shows how the same day corresponds to different periods: it can be the 2nd of a 4*65 division of the tonalpohualli ; the 2nd of 5*52; the 4th of 10*26; the 5th of 13*20; the 7th of 20*13; the 18th of 52*5.

Knowing that each period is likely to be dominated by a different deity gives an idea of the possible superposition of influences.

We don't know whether all tonalpohualli arrangements were used together for every divination or whether there was some form of specialization. Certain types of tonalpohualli could have been used for certain consultations only, this seems to have been the case for merchants, newborns or marriages, but apart from these examples there is nothing to show this.

Analysis of the operation of the tonalpohualli has highlighted a certain complexity in the data that readers of the tonalamatl had to manipulate in order to exercise their divination skills. It is likely, however, that this complexity must have been greater than that seen so far, for at least four reasons:

1) Even if the gods are grouped together under a single name, e.g. Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl..., as if they were the same entity, this only represents a practical solution. Indeed, depending on where the deity is found in a codex, his appearance may be sufficiently different to suggest that these dissimilarities must have affected the powers attributed to him over a given period of time. All these nuances and differences are not taken into account here, but the same was not to be said for the tonalpouhque.

2) only deities related to days have been considered here, but there are other signs whose mantic value should be taken into account. Unfortunately, their role is still unclear[30].

3) the symbolism of colors and directions has not been taken into account here.

4) the tonalamatl were not the only material element involved in the predictions[31]. Indeed, authors such as Durán[32] and Ruiz de Alarcón[33] seem to indicate that corn kernels were also used in conjunction with the tonalamatl or a cloth, thus introducing an element of chance into this complex mechanism.

Marc Thouvenot, honorary CNRS researcher

* Thanks to Carmen Herrera (DL, INAH), Sybille de Pury (CELIA, CNRS) and Jean-Michel Hoppan (CELIA, CNRS) for their observations and comments on an earlier version of this text.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Codex

AUBIN

Aguilera, Carmen, 1981 El Tonalamatl de Aubin, Tlaxcala Códices y Manuscritos, Tlaxcala, 60 p. + facsimile.

BORBONICUS

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen and Luis Reyes García, 1991 El libro del Ciuacoatl, Homenaje para el año de Fuego Nuevo, libro explicativo del llamado Códice Borbónico, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 251 p. + facsimile.

BORGIA

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen and Luis Reyes García, 1993 Los templos del cielo y de la obscuridad, Oráculos y liturgia, libro explicativo del llamado Códice Borgia, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 294 p. + facsimile.

FLORENCE

1979 Códice Florentino. El manuscrito 218-220 de la colección Palatina de la Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Mexico, Giunti Barbéra & Archivo General de la Nación, 3 vol, facsimile.

TELLERIANO-REMENSIS

Quiñones, Eloise, 1995 Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Ritual, Divination, and History in a Pictorial Aztec Manuscript, Foreword by E. Le Roy Ladurie, illustration by M. Besson, Austin, University of Texas Press, 365 p.

TUDELA

Tudela de la Orden, Jose, 1980, Códice Tudela, Madrid, Ediciones Cultura Hispanica del Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana, 315 p. + facsimile.

VATICANUS A

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen and Luis Reyes García, 1996 Religión, costumbres e historia de los antiguos Mexicanos, Códice Vaticano A, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 238 p. + facsimile.

VATICANUS B

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen and Luis Reyes García, 1993 Manual del adivino, Códice Vaticano B, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 382 p. + facsimile. + facsimile.

Authors

Aguilera, Carmen

1981 El Tonalamatl de Aubin, Tlaxcala Códices y Manuscritos, Tlaxcala, 60 p. + facsimile.

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen

1994 La pintura de la muerte y de los destinos, libro explicativo de llamado Códice Laud, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 318 p.

Anders, Ferdinand, Maarten Jansen and Luis Reyes García

1991 El libro del Ciuacoatl, Homenaje para el año de Fuego Nuevo, libro explicativo del llamado Códice Borbónico, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 251 p. + facsimile.

1993 Los templos del cielo y de la obscuridad, Oráculos y liturgia, libro explicativo del llamado Códice Borgia, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 294 p. + facsimile.

1993 Manual del adivino, Códice Vaticano B, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 382 p.

1996 Religión, costumbres e historia de los antiguos Mexicanos, Códice Vaticano A, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 238 p. + facsimile.

Durán, Fray Diego

1995 Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e Islas de Tierra Firme, Estudio preliminar de Rosa Camelo y José Rubén Romero, México, Cien de México, t. 1: 651 p. + 62 plates, t. 2: 293 p. + 56 plates.

Eisinger, Marc.

1994 CF_INDEX: Index lexical du texte nahuatl du Codex de Florence, SUP-INFOR, www.sup-infor.com

G.D.N.

2020 Grand Dictionnaire du Nahuatl, https://cen.sup-infor.com/#/home/gdn

León-Portilla, Miguel

1992 Le livre astrologique des marchands, Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, Edition établie et présentée par Miguel León-Portilla, translated from Spanish by Myriam Dutoit, Paris, La Différence, 255 p.

Motolinía, Fray Toribio de Benavente

1971 Memoriales o libro de las cosas de la Nueva España y de los naturales de ella, Edición preparada por Edmundo O'Gorman, México, UNAM, 591 p.

Nowotny, Karl-Anton

1977 Codex Borgia, French translation by Jacqueline de Durand-Forest and Edouard-Joseph de Durand, Paris, Club du Livre, 51 p.

2005 Tlacuilolli, Style and Contents of the Mexican Pictorial Manuscripts with a Catalog of the Borgia Group, Translated and Edited by G.A. Everett & E. B. Sisson, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 394.

Quiñones, Eloise

1995 Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Ritual, Divination, and History in a Pictorial Aztec Manuscript, Foreword by E. Le Roy Ladurie, illustration by M. Besson, Austin, University of Texas Press, 365 p.

2004 " Divination dans le Codex de Florence ", Le Mexique préhispanique et colonial, Hommage à Jacqueline de Durand-Forest, Textes réunis et publiés par Patrick Lesbre et Marie-José Vabre, Paris, L'Harmattan, 409 p.

Reyes García, Luis

1997 Dioses y escritura pictográfica, Archeologia Mexicana, N° 23, p. 24-33

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de

1950-1982 Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, translated and edited by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. School of American Research and University of Utah, Salt Lake City, 13 vols.

1969 Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España. México, Porrúa, 4 vol.

1979 Códice Florentino. El manuscrito 218-220 de la colección Palatina de la Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Mexico City, Giunti Barbéra & Archivo General de la Nación, 3 vols, facsimile.

1989 Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España. Introducción, paleografía, glosario y notas de Josefina García Quintana y Alfredo López Austin, México, Cien de México, 2 vol.

Seler, Eduard

1988 Comentarios al Códice Borgia, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 3 vol.

TEMOA

2020 Temoa, Computer program, https://cen.sup-infor.com/#/home/temoa

Thouvenot, Marc & Paul Fisher

2021 Tonalpohua, Computer program, https://tonalpohua.sup-infor.com/

Wimmer, Alexis

2005 Dictionnaire de la langue nahuatl classique, Paris, https://cen.sup-infor.com/#/home/gdn

Notes

[1] "DE LA ASTROLOGIA JUDICIARIA O ARTE DE ADIVINAR QUE ESTOS MEXICANOS USABAN PARA SABER CUALES DIAS ERAN BIEN AFORTUNADOS Y CUALES MAL AFORTUNADOS, Y QUE CONDICIONES TENDRIAN LOS QUE NACIAN EN LOS DIAS ATRIBUIDOS A LOS CARACTERES O SIGNOS QUE AQUI SE PONEN, Y PARECE COSA DE NIGROMANCIA, QUE NO DE ASTROLOGIA

CAPÍTULO I, del primero signo, llamado ce cipactli, y de la buena fortuna que tenían los que en él nacían, ansí hombres como mujeres, si no la perdían por su negligencia o floxura

Aquí comienzan los caracteres de cada día, que contaban por trecenas. Eran trece días en cada semana, y hacían un círculo de doscientos y sesenta días, y después tornaban al principio." (Sahagún, 1989, p. 233)

[2] "contiene veinte caracteres multiplicado trece veces". (Sahagún, 1989, p. 231)

[3] It is also possible to access the content of QR codes by typing https://tonalpohua.sup-infor.com/?context= plus the word indicated next to it, in this case: https://tonalpohua.sup-infor.com/?context=numbers

[4] In their commentary on Codex Vaticanus B the three authors, Anders-Jansen-Reyes, point out regarding the first hypothesis: "En un calendario que se cimienta en la eterna repetición de un ciclo de 260 días, periodo que coincide -por lo menos conceptualmente- con el embarazo, el día del nacimiento de un niño tiene el mismo nombre que el día en que fue concebido (exactamente un ciclo de 260 días antes). Y esto, naturalmente, es muy significativo en términos mánticos" (p. 51)

The same authors also relate the number 13 to cosmology: "Para los pueblos mesoamericanos la superficie terrestre se divide en cinco puntos cardinales: las cuatro direcciones más el centro. Contando también cuatro direcciones en el inframundo, llegamos al numero 9, asociado con el Reino de la Muerte. Agregando otras cuatro unidades para las direcciones celestes, llegamos al número 13, asociado con el cielo y con la estructura del cosmos en general. Trece son los rumbos que integran el universo, el macrocosmos..."

[5] CF, IV, 4. Sahagún, 1989, p. 231.

[6] See GDN.

[7] Incidentally, the two words can enter into composition as in the expression cemilhuitonalli which means "the destiny of a day".

[8] According to Motolinía (p. 60): "A esta cuenta la llaman tonalpohualli, que quiere decir, cuenta del sol, porque la interpretación e inteligencia de este vocablo, largo modo, quiere decir cuenta de planetas o criaturas del cielo que alumbran y dan luz...."

[9] CF, IV, 19: In ipan ei atl tonalli: mjtoa qualli, ioan amo qualli we also find for unfortunate signs the expression tequantonalli which means the sign of wild beasts, those that can eat man.

[10] "pero era menester para gozar desta habilidad que fuese muy devota a su signo y hiciese penitencias todos los días que reniaba" (Sahagún, 1989, p. 243).

[11] Quoted by Anders-Jansen-Reyes: "También Motolinía afirma que al elegir un dia para una ceremonia, se tomaba en cuenta el valor numérico. Se consideraba como 'mal agüero', o 'mala casa' el día que caía en pares, como cuatro, seis, ocho; pero los nones eran buenos. Y si la persona había nacido en día de pares, para su fiesta buscaban una 'casa' de nones, contando sobre el numero del día en que había nacido, porque pares y nones siempre son nones. Y por el contrario, si había nacido en día o casa de nones, elegían día de pares, para que todos juntos fuesen nones" (Motolinía, 1971, p. 341; Mendieta, 1971, p. 158) (Vaticano B p. 86)

[12] "Para más inteligencia de lo que queda dicho, y por decir, es de saber que en aquellas veinte figuras que para los días del mes estaban señaladas, parte de ellas era buena, de buen pronóstico, y parte, malas, y parte, indiferentes, las cuales son las siguientes

Cabeza de sierpe, Casa, Lagartija, Venado, Buharro, Perro: estos eran signos buenos y de buenos sucesos para los que en ellos nacían.

Los indiferentes eran: Conejo, Mono, Caña, Tigre, Aguila, Rosa, Curso. Llamaban a estos signos indiferentes, porque los que en ellos nacían participaban de bien y de mal; unas veces se verían en prosperidad, y otras veces, en pobreza, sujetos a sucesos malos y buenos.

Los signos malos y de mal pronóstico son: Viento, Culebra, Agua, Matorral, Pedernal, Aguacero, Muerte. Estos siete signos o figuras eran tenidos por malos, para los que nacían en ellos. Y para que más claro lo veamos --aunque me tome un poco de trabajo- quiérolo poner y demostrar, relatándolo por cada figura, conforme a como lo hallé pintado en un viejo y antiguo papel, lleno de tantas y feas figuras de demonios, que me puso espanto. (Duran, I, 228-29)

[13] Comparison made on the assumption that in the latter every day name must be assigned a number 1.

[14] Estos naturales de toda Nueva España tuvieron y tienen gran solicitud en saber el día y hora del nacimiento de cada persona para adivinar las condiciones, vida y muerte de los que nacían. Los que tenían este oficio se llamaban tonalpouhque, a los cuales acudían como a profetas cualquier que le nacía hijo, hija, para informarse de sus condiciones, vida y muerte. (Sahagún, 1989, p.231-32)

[15] The authors of recent tonalamatl publications, Anders-Jansen-Reyes, state: "Por sus funciones mánticas, rituales y reguladoras, el calendario tiene que ver con todos los aspectos de la vida. Lo muestra su uso actual, entre mixes, quichés y otros pueblos- y se ve también en los textos de la época virreinal. Las funciones básicas del calendario son: pronosticar cuales influencias gobernaran la vida de un ser humano, por los múltiples aspectos del día en que nace; cual será su carácter y su suerte; de que circunstancias se tendrá que cuidar, y a cual dios tendrá que acudir;seleccionar el día propicio para comenzar alguna empresa, el trabajo en la milpa, un viaje, un matrimonio, una ceremonia, una ofrenda, y diagnosticar las eventuales causas espirituales de una desgracia, como una enfermedad, por el día en que se manifestó el mal, o interpretar lo que nos anuncia un sueño o un agüero, e indicar el remedio correspondiente. (Códice Vaticanus B p. 45)

[16] Quilchiuhqui: in quilchiuhqui tlatocani, tlapixoani, quauhtocani, tlaaquiani, tlaani, elimiquini, tlamoloniani, tlacoçolteuhtlaliani. In qualli quilchiuhqui, tlanêmâtcachioani, tlaiuiachioani, iiel, tlâceliani, tlamocuitlauiani, tlacenmatini, mozcaliani, amoxmatini, tonalpoani, metztlapoani xippoani. (CF X, 42)

[17] A search, with TEMOA, on a whole corpus of texts allows us to affirm this.

[18] Alexis Wimmer's dictionary in GDN.

[19] The presence of the verbs tlatoa and italhuia "to speak" obviously brings to mind the "speaking days" identified by Barbara Tedlock.

[20] "reinaba la diosa Venus, que le llamaban Tlazultéotl" (Sahagún, 1989, p. 257)

[21] Eloise Quiñones "Divination in the Florence Codex" p. 129

[22] This tabular organization can be compared, in principle, to that found in plates 53-54 of the Codex Borgia, plates 1 to 8 of the Codex Cospi or the Codex Vaticanus B.

[23] Tonalamatl Aubin f. 20, mentioned by Anders-Jansen-Reyes in their commentary on the Codex Borgia p. 65. This is because while 260 is not divisible by 9, 261 is.

[24] Anders-Jansen-Reyes, 1993, p. 105-108

[25] Anders-Jansen-Reyes, 1993, p. 347-351

[26] Aguilera, Carmen, 1981.

[27] List compiled by E. Seler and taken up by C. Aguilera, 1981, p. 21.

[28] Anders-Jansen-Reyes, 1993, p. 301.

[29] The tonalpohualli may be presented either in extenso or in abbreviated form, as stated by Nowotny (1977, p. 22), who compiled a list for the Codex Borgia.

[30] See in particular Luis Reyes García's article on this theme in Archeologia Mexicana, 1997, N° 23, p. 24-33.

[31] Plate 21 of the Codex Borbonicus features the creators of tonalpohualli, Oxomoco and Cipactonal, and shows Oxomoco throwing corn kernels.

[32] "El astrólogo y sortílego hechicero sacaba luego el libro de sus suertes y calendario, y vista la letra del día, pronosticaban y echaban suertes y decíanles la ventura, buena o mala, según había caído la suerte....junto a estos dioses estaban pintadas las letras de los días de su calendario; sobre este papel echaban suertes y, conforme caía, pronosticaban. Y si caía la suerte sobre el dios de la vida, decían que era de larga vida; si caía sobre la muerte, decían que habían de vivir poco, y así de los demás, que por prolijidad, no pongo en cada uno en particular. Baste saber que, si había de ser rico, o pobre, o valiente, o animoso, o cobarde, religioso, o casado, o ladrón, o borracho, o casto, o lujuriosos, allí en aquella pintura y suertes lo hallaban, y avisaban los padres y parientes, haciéndoles salvas primero y platicas largas y retóricas, salían después con dos docenas de mentiras y fábulas, afirmando cosas que, aun al diablo que les persuadía aquello, le es oculto, pues solo a dios son las cosas futuras presentes.". (Duran, I, 2, p. 228)

[33] Anders-Jansen-Reyes, 1991, p. 184-185.