Writing in Amharic

Amharic is written in Ethiopian characters, representing one of the few ancient African writing systems whose vast literary corpus has been attested for almost two millennia. This script, which has evolved over time, is used mainly, but not exclusively, for the Ethiosemitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Amharic is written in Ethiopian characters representing one of the few ancient African writing systems whose vast literary corpus has been attested for almost two millennia. This script, which has evolved over time, is used mainly, but not exclusively, for the Ethiosemitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Originally, it was used to write Guèze (or classical Ethiopian), the oldest known Ethiosemitic language, which ceased to be spoken in the second half of the 1st millennium CE, but remains the liturgical language of the täwahedo Orthodox Church of Ethiopia.

Until the late 19th century, Gueze was the only language written at the royal court, where Amharic served as the lingua franca. In the 13th or 14th century, Amharic took over the Ethiopian script from Guèze, but was written only sporadically until the early 20th century, when it became the language of instruction in elementary school and was declared the national language. Today, it is the working language of the Ethiopian government and is still widely used as a second language throughout Ethiopia, serving as a lingua franca.

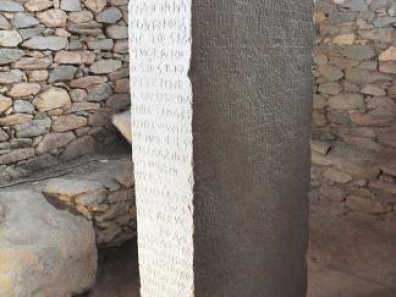

The earliest attestations of writing in Ethiopia and Eritrea are pseudo-Sabaean inscriptions in consonant script from South Arabia dating from the 8th/7th centuries BC.

Credits: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient_Blocks_With_Sabaean_Inscriptions,_Yeha,_Ethiopia_(3146498586).jpg

They were most likely composed by Ethiosemitic speakers for whom Sabaean was a learned language, as these inscriptions contain linguistic features not found in the Sabaean of southwest Arabia. Ethiopian abjad (or consonant script), which first appeared to write Geze between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, is clearly a modification of South Arabian abjad. It was considerably modified in the 4th century, when it switched from an abjad (i.e. unvoiced) to an abugida, i.e. a syllabic script in which a grapheme, called a syllabograph (or syllabogram), combines a consonant and a vowel (or may represent a bare consonant).

The strong Greek influence in the region, from 300 BC to 600 AD, most likely triggered further modifications to Ethiopian writing, in particular the incorporation of Greek letters as signs for numerals, the switch from boustrophedon to left-to-right writing, and probably the invention of two additional syllabographs, ፐ ⟨pä⟩ and ጰ ⟨p'ä⟩.

Ethiopian and some Indian scripts belong to the same type of writing, which uses the abugida system, i.e. a basic syllabograph, vocalized with an open and not a back vowel (a or ä), and modified by diacritical marks for other vowel values. Inscriptions in a Brāhmī script, as well as graffiti in Ethiopian abjad from the period between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD have been discovered in a cave at Socotra. This shows that Indian writing may have been adopted during the development of Ethiopian abjad. However, it is also argued that Ethiopian and Meroitic scripts differ to some extent from Indian scripts, so that they must be regarded as independent innovations. Among the Semitic languages, the Ethiopian script is the only one based on an abugida.

1. Fundamental features of the Ethiopian script

1.1 From Ethiopian abjad to abugida

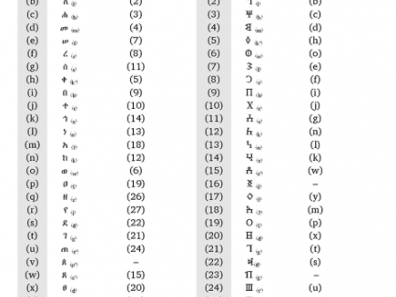

The Ethiopian script is derived from the Sudarabic script, an abjad composed of 29 consonantal graphemes, which were written from right to left or in boustrophedon. Table 1 shows the graphemes of ancient Ethiopian abjad and their correspondence with Sudarabic. With the exception of a few ancient inscriptions, the direction of writing in Ethiopian script is systematically left to right.

The consonant graphemes in Table 1 are arranged according to their order in the respective scripts.

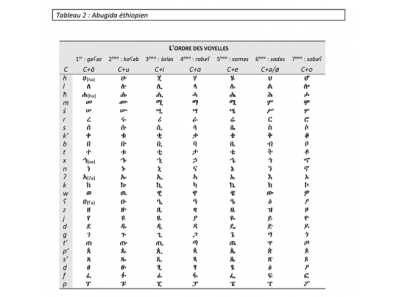

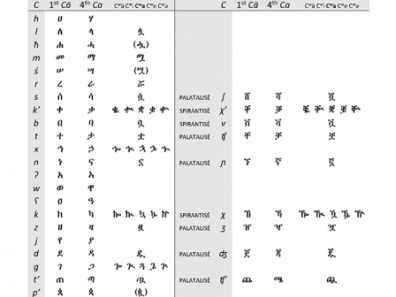

Not long after its first attestations in the 4th century, the Ethiopian consonant script evolved into abugida. The consonants in Table 1 became basic syllabographs, i.e. fixed syllables with the consonant plus vowel sequence ä, to which diacritical marks were added to write syllables with the remaining vowels u, i, a, e, ǝ/ø, o.

For example, the consonant በ ⟨b⟩ of Ethiopian abjad has become the basic syllabograph ⟨bä⟩. Sequences of b followed by other vowels are marked by circles and horizontal or vertical dashes next to each other. Thus, bu is written by adding a stroke to the middle of the right-hand side ቡ ⟨bu⟩, bi by a stroke to the bottom of the right-hand side ቢ ⟨bi⟩, ba by a vertical line on the right ባ ⟨ba⟩, be by a circle at bottom right ቤ ⟨be⟩, and bo by a vertical line to the left ቦ ⟨bo⟩. Sequences with the vowel ǝ or without a vowel (i.e. a bare consonant) are written by the same modification, e.g. for b (ǝ) a stroke is added to the middle of the left side ብ ⟨bǝ/b⟩. As Table 2 shows, vowel diacritics are regular for some grapheme blocks, but variable for others.

The vowel sequence is invariable in Ethiopian writing. It begins with the basic syllabograph Cä, which is called gǝʔǝz or gǝʕǝz. Next come syllabographs marked for vowel u, i, a, e, ǝ/ø, o - which are called by the respective ordinal Guez numbers, i.e. Cu is kaʕǝb 'second (order)', Ci śalǝs 'third (order)', etc.

The graphemes of Ethiopian abjad and abugida are generally called by the syllable they represent, i.e. lä for ለ ⟨lä⟩, mä for መ ⟨mä⟩, etc. Only a few syllabographs, which today represent consonants that have the same pronunciation, are called by their names by way of clarification, e.g. halleta ha for ሀ ⟨hä⟩ vs ħamär ha for ሐ ⟨ħä⟩ - both pronounced [ha].

The arrangement of syllabographs in an alphabet book is called fidäl. The syllabographs in the primer in Table 2 and the abjad in Table 1 are arranged in a sequence that we call hahu -according to the first two syllabographs, either ሀ ⟨ha⟩ - ሁ ⟨hu⟩. There's also a primer in which the syllabographs are arranged according to the order of the Northwest Semitic script, but always declined in vowel order. It begins with the sequence አ ⟨ʔa⟩ - ቡ ⟨bu⟩ - ጊ ⟨gi⟩ - ዳ ⟨da⟩ hence its name abugida.

1.2 Number graphemes

The number letters of the Greek alphabet have been incorporated into the Ethiopian script as number graphemes. They are surrounded by an upper and lower line (Table 3) to avoid confusion with other graphemes. The Ethiopian script has no grapheme for the zero '0'.

Numeric graphemes encode numbers by adding up the individual numeric values of the digits, namely the unit, the ten, the hundred, going from the largest number to the smallest. For example, the number '123' is written ፻፳፫ ⟨100+20+3⟩, i.e. the sum of 100 plus 20 plus 3. Numbers between 200 and 900 mark the actual value of 'hundred' by the digit preceding the grapheme ፻ ⟨100⟩, for example '523' is encoded ፭፻፳፫ ⟨5x100+20+3⟩, in which 5 is multiplied by 100, to which 20 and 3 are added.

Today, these Ethiopian numerals are used less and less, gradually replaced by Indian numerals.

1.3 Punctuation marks

In early Ethiopian inscriptions, words were divided by a vertical bar ⟨ | ⟩, as in Sudarabic. Later, it was replaced by a colon ⟨ | ⟩. Other punctuation marks include the period ⟨ ። ⟩, a paragraph separator ⟨ ፨ ⟩, several signs for enumerations, i.e. a comma ⟨ ፣ ⟩, a colon ⟨ ፥ ⟩ or ⟨ ፦ ⟩ and a semicolon ⟨ ፤ ⟩. With the exception of the word separator, these punctuation marks are not used consistently. Currently, the word separator is often replaced by an empty space. Other punctuation marks common in European writing systems have also been incorporated, including the question mark ⟨? ⟩, the exclamation mark ⟨ ! ⟩, and the quotation marks ⟨ " " ⟩.

2. Modifications to abugida

The vocalization of Ethiopian abjad into abugida in the 4th century is followed by a number of other modifications, namely the invention of syllabographs for labialized velars (which were later extended to non-velar consonants), and the invention of syllabographs for palatal or spirantized consonants. These modifications cannot always be dated, but seem to be due to the adaptation of the Ethiopian script to write Amharic.

2.1 Labialized consonants

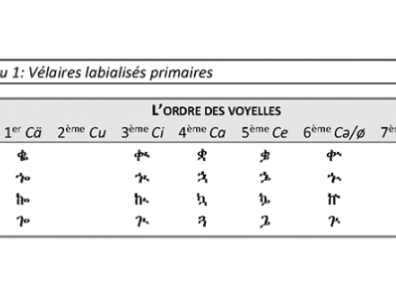

Ethiosemitic has a series of primary labialized velars kʷ, gʷ, k'ʷ, xʷ, which are not found in other Semitic languages. Their syllabographs are derived from the corresponding ordinary velars k, g, k', x/h. Note that this series systematically lacks syllabographs for the vowels u and o, i.e. *Cʷu and *Cʷo, as Table 4.

shows.

On the basic syllabograph, labialization is marked by a circle attached to the middle of the right side (ex. ቀ ⟨k'ä⟩ becomes labialized ቈ ⟨k'ʷä⟩), and by an extension of the diacritical marks for syllabographs with the vowels a and e, ቃ ⟨k'a⟩ becomes ቋ ⟨k'ʷa⟩, and ቄ ⟨k'e⟩ becomes ቌ ⟨k'ʷe⟩. The syllabographs for velars labialized with the vowels i and ǝ/ø are derived from the basic syllabograph for simple velars by adding two different types of curved strokes on their upper right-hand side. For example, the syllabograph ቀ ⟨k'ä⟩ is the basis of the labialized consonants ቊ ⟨k'ʷi⟩ and ቍ ⟨k'ʷ(ǝ)⟩.

Later, syllabographs were introduced for labialized non-velar consonants, which have only one grapheme, namely Cʷa, derived from the 5th order of its ordinary syllabograph, as in Table 5.

More recently, even ħ, ś, p', and secondarily palatalized and spirantized consonants have acquired syllabographs for the sequence C+ʷa.

2.2 Palatal consonants

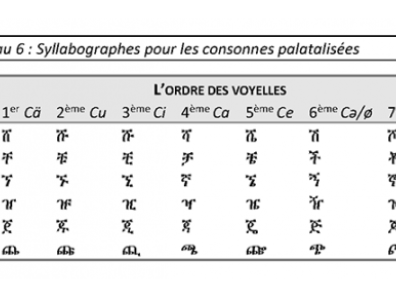

When Ethiopian script was adapted for writing Amharic in the 14th and 15th centuries, six additional sets of syllabographs for palatal consonants ʃ, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ, ʧ', ɲ were created by modifying their simple counterpart syllabographs, as shown in Table 6.

Palatalization is mainly marked by a stroke at the top of the syllabograph of the corresponding alveolar consonant, for example, ሸ ⟨ʃä⟩ is derived from ሰ ⟨sä⟩, ሹ ⟨ʃu⟩ from ሱ ⟨su⟩, etc.

The syllabograph for ʒ is characterized by two distinct strokes attached to the two upper ends of the syllabograph for z, i.e. ዘ ⟨zä⟩ becomes ዠ ⟨ʒä⟩. Only the ʧ' syllabograph marks palatalization with circles attached to the three extensions, i.e. the ጨ ⟨ʧ'ä⟩ palatalized derives from the ጠ ⟨t'ä⟩ simple.

2.3 Additional syllabographs

The Amharic script triggered further changes and innovations in Ethiopian abugida. In Gueze, the basic syllabographs of the fricatives h, ħ, x, ʕ, and the glottal stop ʔ are irregularly pronounced with the vowel a instead of ä. Consequently, there was no written representation of the syllables hä and ʔä. As hä (or its variants χä~xä) is fairly common in Amharic, it began to be written by the syllabograph ኸ ⟨χä⟩, which was derived by a stroke at the top of ከ ⟨kä⟩. The derivation of the consonant h (or consonants χ and x) from k represents the diachronic spirantization of k into h (via x).

The creation of the marginal syllabograph ኧ ⟨ʔä⟩ by attaching a line to አ ⟨ʔa⟩ is probably related to this. The syllabograph ኧ ⟨ʔä⟩ is never modified by a vowel diacritic, as it only appears in the interjection ኧረʔärä "Ah bon!?" (expressing surprise).

Although the syllabographs ቨ ⟨vä⟩ and በ ⟨bä⟩ are also related, ቨ ⟨vä⟩ does not represent the spirantized b, as v is not a native ethiosemitic phoneme, but restricted to loanwords. It was probably created by Catholic missionaries in the 17th century, who used it to transcribe Portuguese.

All the syllabographs in Table 2 represent different phonemes in Guèze spoken up to the 6th century AD. As not all the phonemic distinctions of Gueze exist in Amharic and other Ethiosemitic languages, some of the original syllabographs were used interchangeably to represent the same consonant. In particular, አ ⟨ʔa⟩ and ዐ ⟨ʕa⟩ now both represent the glottal stop ʔ, ሀ ⟨ha⟩, ሐ ⟨ħa⟩ and ኀ ⟨xa⟩ are variants for the fricative h, ሠ ⟨śä⟩ and ሰ ⟨sä⟩ for the sibilant s and ፀ ⟨ḍä⟩ and ጸ ⟨s'ä⟩ for the ejective s'.

Therefore, unless etymology is considered, the same word may appear differently in writing, e.g. ደኅና ⟨dä.x.na⟩, ደሕና ⟨dä.ħ.na⟩ or ደህና ⟨dä.h.na⟩, all of which are pronounced dähna "good" in Amharic. Several attempts to eliminate variants in the Amharic script have so far failed.

Delombera Negga, Serge Dewel and Ronny Meyer

Delombera Negga, senior lecturer in Amharic language and linguistics.

Serge Dewel, PhD in Ethiopian history. Researcher in contemporary Ethiopian history.

Ronny Meyer, lecturer in Amharic. Doctor in African philology.

Reference

Meyer, Ronny. 2016. "The Ethiopic script: linguistic features and socio-cultural connotations". Oslo Studies in Language 8(1). 457-492.