When decency becomes a moon head and the Master an ear: linguistics and its place in the teaching of Vietnamese at Inalco

In this way, the acquisition of linguistic skills - which we do not wish to glorify any further here - is reduced, if not to that of a simple communication tool, then at least to that of a secondary tool, or one that serves other disciplinary and scientific knowledge. To take the case of Vietnamese alone, some teachers fear that most students attach excessive, even obsessive, importance to mastery of the language and, in particular, to phonetic correction, when these should be purely a matter of practice and execution. According to the former, being in the presence of a native-speaker teacher, even one not trained to teach the language, is a guarantee of unwavering fluency, just as cloistering oneself in a language lab, headphones on, or going on a total immersion trip abroad for a short time, is enough to give students flawless language autonomy.

Teaching vs. the field: misunderstanding guaranteed?

While these preconceptions are not entirely unfounded, they do reflect a somewhat simplistic view of language and its appropriation. The testimonies of a good colleague of the author of this article speak volumes about the harmful consequences of such a conception. With a bachelor's degree in Vietnamese, which she brilliantly completed in parallel with her doctorate in the humanities and social sciences, the young teacher-researcher currently working at a major Parisian university has, for several years now, been required to carry out short but regular research visits to Vietnam. However, reality outweighs fiction, and it wasn't long before the first visit opened the eyes of the ex-doctoral researcher, who discovered to her dismay that, despite her excellent marks in language, her operational skills were as incomplete as ever.

Totally helpless in the face of the southern dialect she wasn't accustomed to hearing during her Vietnamese classes, and the desperate stares of her interlocutors, the young doctor becomes baffled and further muddles her words, unable to place tones correctly on vowels, slacking off on all final consonants and omitting terms of address. The famous Nguyễn retains its French form N'guyen; Trang (Vietnamese first name meaning "decency") becomes Trăng (a name designating the moon in its physical dimension) ; Thầy (Master) becomes Tai (ear) and Mặt (face) is understood to mean Mặc (wearing a garment).

Vietnamese eventually gives way to English and the conversation turns to grammar, this time with great emphasis on the need to use con (classifier applied to animate) and not cái (used with inanimate entities) in the case of the nouns đường (path) and phố (street) ; to which is added the systematic insertion of đã, đang, sẽ before verbs to mark past, present and future trials.... Today, the colleague seems to recognize that the Vietnamese grammars of the 40s and 50s, modeled on French, not only gave her an erroneous vision of the language, but also provided her with highly unworkable knowledge that was sometimes completely disconnected from Vietnam's linguistic and socio-cultural reality. After further attempts, all in vain, during her final fieldwork, she has now renounced the idea of including a degree in Vietnamese in her curriculum vitae.

This story is not an isolated one. Many students of Vietnamese have experienced similar setbacks. However trivial they may seem at first glance, they suggest that beyond a question of phonological deafness (Polivanov 1931, Troubetzkoy 1967/1939) and defective pronunciation, to which would be associated the cognitive functioning of the allophone speaker and the perceptual strategies implemented by the latter in processing phonetic variability (Magnen et al. 2005, Magnen 2009), ignorance of the general functioning of the target language and lack of awareness of the fundamental properties of the source language would all be factors inhibiting language appropriation. It is precisely for this reason that linguistics has its rightful place at Inalco, and must play its full part.

The place of linguistics

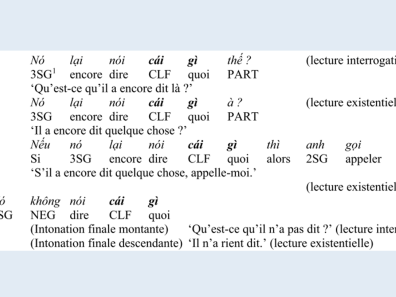

The linguistic study of Vietnamese at Inalco, whether theoretically oriented or applied to its teaching, is part of the wider context of the investigation of Asian languages and lies at the crossroads of Southeast Asia and the Pacific and East Asia. It takes an areal, typological, comparative and theoretical perspective, combining descriptions, formalizations and applications. One of the current research themes along these lines concerns the study of interrogative expressions of the wh-/qu- type in four East Asian languages (Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese) (Pan et al. 2018a, b). Indeed, Vietnamese lexical items such as ai (who), cái gì (what), ở đâu (where), thế nào (how), bao nhiêu (how much), etc., like their Chinese, Korean and Japanese counterparts, can, depending on the context, be given an interrogative or existential reading:

The hypothesis defended by Pan et al. (2018a, b) is that both readings are formally legitimized in contexts described as "strong", as exemplified by the statements in (1). The ambiguity observable in an example like (2) emerges, meanwhile, only in so-called "weak" contexts, in which case it can be removed by appropriate prosodic structures. The comparison of similar data from the four languages studied suggests that they have various legitimization strategies: morphological, syntactic and prosodic. It also highlights the special status of prosody in this type of phenomenon, insofar as it is activated only when the other two mechanisms are unavailable.

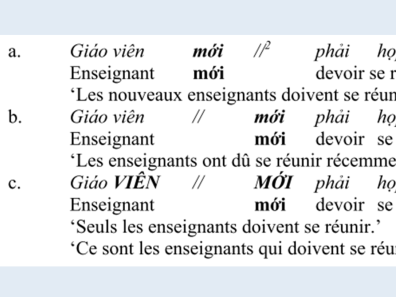

The interaction between prosody and syntax also proves relevant in the processing of transcategorial units (cf. Do-Hurinville & Dao 2018, Dao 2019), such as mới in (3), where explicit prosodic markings (pause, accentuation) give rise to three different syntactic-semantic configurations:

Prosody and its various manifestations are, one suspects, generative of meaning (and vice versa). Thus contrastive focus and prosodic demarcations in (3), which thus reveal the syntactic boundary between the subject nominal group and the verbal group, also constitute primordial indicators in the identification of the parts of speech of Vietnamese, due, in particular, to the isolating character of the latter. The categorical plasticity illustrated supra by mới leads us to believe that the interpretative process is above all functional and contextual. The attentive reader (uninfluenced by categories derived from the Indo-European grammatical tradition) might wonder whether this isn't rather a case of homonymy, since the transition between a quality verb, in epithetical use (to be-new), a temporal co-verb expressing the recent past (recently) and a restriction marker associated with the focusing effect of prosody (seul(ement), c'est...qui) is so unclear. Here, we simply refer the interested reader to the aforementioned works, the transversality of a semantic invariant between descriptive, temporal and modal domains being an extremely frequent phenomenon in the world's languages.

Transcategoriality seems to be an areal feature observable in Southeast Asia and the Pacific and in East Asia. One of its best incarnations would be the use of kinship terms and spatial demonstratives as "personal pronouns" during social interactions, during which the identity of discursive roles can only be determined contextually. Their mediation by "family" lexis and spatial deixis amounts to a re-exploitation of lexical units originally intended for other purposes. This form of "formal parsimony", closely linked to the field of linguistic politeness, could be seen as resulting from a process of (inter)subjectification (Dao 2020a). This raises the question of the link between (inter)subjectivity and prosodic parameters. Recent research by the author of this article (Dao 2020b) attempts to show that politeness is jointly conveyed in Vietnamese by a play of tonal symbolism and by an explicit "semantico-pragmatic" concordance between the system of final particles and that of pronouns and terms of address. One of the implications of this analysis is that the realization of these item classes is subject to syntactic-pragmatic constraints, contrary to what the optional nature of pronoun use in Vietnamese would suggest. The proposed analysis also makes it possible to account for the recent emergence of a new linguistic expression of acquiescence in this language.

These few problems, like many others, are all linguistic "incongruities", mostly invisible in writing and virtually absent from Vietnamese grammars, which are likely to pose serious obstacles to the foreign learner. They deserve to be integrated into the Vietnamese teaching program at Inalco, something that has been in place for almost a year now. Conceived as a specialization of the Introduction to the Linguistics of Southeast Asian and Pacific Languages course, created on the initiative of our late colleague Joseph Deth Thach; and the seminar Multilingualism and Society in Southeast Asia, Vietnamese linguistics courses adopt a resolutely contrastive approach and emphasize intra- and inter-dialectal variations, while remaining faithful to their translinguistic perspective. From this point of view, the acquisition of language skills is based as much on the internalization of foreign structures as on an awareness of the convergences and divergences between different linguistic and socio-cultural systems, whether these concern the source and target languages, or the idioms of which the language studied is but a variety.

Huy-Linh Dao

Lecturer in general, Vietnamese and French linguistics

Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l'Asie Orientale (CRLAO - UMR 8563, CNRS-EHESS-Inalco)

Notes

[1] Abbreviations: 1SG (1st person, singular), 2SG (2nd person, singular), 3SG (3rd person, singular), CLF (classifier), NEG (negation), PART (final particle).

[2] The double slash represents a prosodic caesura and capital letters accented units.

References

- Dao, H.L. (2020a). "Espace (inter)subjectif entre syntaxe et discours : perspectives asiatiques et regards croisés avec le français", Research seminar of the Équipe de Recherche Interdisciplinaire sur les Aires Culturelles (ERIAC EA 4705) : Fonctionnements linguistiques et intersubjectivité, Université de Rouen Normandie, March 3, 2020.

- Dao, H.L. (2020b). "Linguistic marking of politeness in modern Vietnamese: between phonetic symbolism and radical pro-drop", JE Approche comparative de la politesse linguistique en français et dans des langues et cultures éloignées, Université Paris Nanterre, January 24, 2020.

- Dao, H.L. (2019). "From lexicon to discourse: lại between generalized predication and discursive memory". Peninsular: Interdisciplinary Studies on Peninsular Southeast Asia, 77, 2018 (2), 113-150.

- Do-Hurinville, D.T. & Dao, H.L. (2018). "Transcategoriality and isolating languages: The case of Vietnamese". In Sylvie H., Do-Hurinville D.T. & Dao H.L. (eds.), Transcategoriality: A crosslinguistic perspective, Special issue of Cognitive Linguistic Studies 5:1, John Benjamins, 8-38.

- Corre, E., Do-Hurinville, D.-T. & Dao H. L. (2020). The Expression of Tense, Aspect, Modality and Evidentiality in Albert Camus's L'Étranger and Its Translations: An empirical study, Coll. Lingvisticae Investigationes Supplementa, 35, John Benjamins. 389 p.

- Magnen, C., Billières, M. & Gaillard, P. (2005). "Phonological deafness and categorization. Perception of French vowels by Spanish speakers". Revue Parole (33), 9-30.

- Magnen, C. (2009). A dynamic approach to speech perception: categorization of substance and phonetic variability by native French speakers and foreign Spanish speakers. PhD Thesis, University of Toulouse.

- Pan, V. J., Dao, H.L., Choi, J. & Nishio, S. (2018a), "A Comparative Study on Wh-quantification in Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese: An Interface Strategy at Morphology-Syntax-Prosody", XXXIe Journées de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale, INALCO, June 28-29, 2018.

- Pan, V. J.., Choi, J., Dao, H.L. & Nishio, S. (2018b), "Interface Strategy to wh-quantification: A Comparative Approach", The 8th international conference on formal linguistics, Hangzhou, China, November 23-25, 2018.

- Polivanov, E. (1931). "The perception of the sounds of a foreign language". Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Prague, vol. 4, 79-96.

- Troubetzkoy, N. S. (1939). "Grundzüge der Phonologie". Travaux du cercle linguistique de Prague, vol. VII: Prague. (Trad. fr. 1967, Principes de phonologie, Paris: Klincksieck).

https://visosanh.com/thiet-bi-so/kim-tu-dien/10062019-17702.html

(Translation: "I can speak 105 languages, can you?")