Colloque international : "Etre écrivain.e sous Poutine" : Retour sur vingt ans d’histoire littéraire

Etre écrivain.e sous Poutine : Retour sur vingt ans d’histoire littéraire

Appel à communications

Colloque international

Inalco, Paris, 6-7 mars 2025

English version below / Текст на русском ниже

L’invasion à grande échelle de l’Ukraine par la Russie a été perçue par beaucoup comme la fin d’une époque : les espoirs d’une démocratisation de la Russie, de leur essor dans les années 1990 à leur progressive érosion durant l’ère poutinienne, appartiennent désormais au passé. En littérature également, le renforcement de la censure depuis le 24 février 2022 et la vague d’émigration massive qui l’a suivi sembleraient annoncer un retour à la tripartition soviétique : littérature censurée (officielle et autorisée), non-censurée (samizdat et tamizdat), émigrée, avec toutes les nuances qu’il faut apporter à une telle division. Toutefois, sans nier le bouleversement que constitue le 24 février, on peut s’interroger sur la pertinence d’une périodisation aussi tranchée. Le régime se durcit de façon graduelle au moins depuis 2011, et le milieu littéraire russe a réagi à cette évolution. On pourrait ajouter, comme le note Galina Youzéfovitch, que la littérature est un « art à réaction lente » (искусство медленного реагирования) et que l’onde de choc de la guerre en Ukraine (et peut-être même de celle qui a commencé en 2014) n’est pas perçue par tous les écrivain.es comme devant remettre en question leurs pratiques.

C’est pourquoi ce colloque vise à donner une vue d’ensemble de la vie littéraire de la fin des années 1990 à nos jours, en remettant en perspective les bouleversements contemporains à la lumière de la guerre : qu’est-ce donc qu’être écrivain.e sous Vladimir Poutine en 2024, par rapport à 1999, à 2011, à 2014 ? Il s’agit de redonner un contexte et une histoire aux positionnements littéraires russes suscités par le début de la guerre : le 24 février 2022, vécu à juste titre comme une rupture majeure, tend à masquer le fait que la question de l’engagement ou du désengagement, personnel ou institutionnel, s’est posée en réalité, après la liberté des années 1990, pendant la totalité de la période poutinienne, celle-ci se caractérisant par la coexistence d’une pression croissante vis-à-vis de la liberté d’expression et d’une diversification de la production littéraire.

Sont suggérées ci-dessous quelques pistes de réflexion.

Une littérature témoin de l’Histoire post-soviétique

- Mémoire littéraire du passé russe récent

- Réécritures de l’histoire, histoire alternative de la Russie et de l’URSS

- Echos entre parcours personnels/récits du quotidien et grande histoire

Si la mémoire des répressions soviétiques dans la littérature contemporaine a fait l’objet de plusieurs études (Jurgenson, Platt) et si ses représentants sont désormais des classiques contemporains (Lebedev, Yakhina, Alexievitch), souvent traduits dans plusieurs langues et largement récompensés, la question de la mémoire de la période post-soviétique, des « folles années 1990 » (лихие девяностые), de la crise constitutionnelle de 1993, de la figure d’Eltsine, des guerres de Tchétchénie, de l’arrivée au pouvoir de Poutine et des attentats de 2000 est beaucoup moins abordée, même si elle constitue la toile de fond de récits intimes où la violence publique et la violence domestique se font écho (Bogdanova, Vassiakina), ou encore le sujet même de l’intrigue dans les romans conspirationnistes et conservateurs d’Alexandre Prokhanov. La représentation des différentes guerres post-soviétiques qui ont précédé ou accompagné la présence au pouvoir de Vladimir Poutine (Guélassimov, Prilépine, Sadoulaïev) mérite également étude.

Nouvelles politisations et dépolitisations de la littérature

- Prises de position politiques en littérature (dans les textes/hors des textes)

- Évolution idéologique/politique d’écrivain.e.s

- Refus explicites ou implicites de se positionner

- Réseaux de sociabilité (revues, librairies) littéraires et politiques

Après la forte polarisation politique des revues littéraires au tournant de la perestroïka, de larges pans de la littérature postsoviétique se sont ostensiblement dépolitisés : la diversification et l’explosion d’une littérature de masse vient faire contre-point à la captation de la culture par l’idéologie durant la période soviétique. Cependant, dans les années 2000 de nouvelles politisations émergent dans le champ littéraire : le courant néoconservateur s’affirme, tandis que des auteurs du camp que l’on appelle en Russie « libéral » (Akounine, Bykov) prennent position dans le débat public. Dans les années 2010, une première vague d’exils a vu des auteurs comme Akounine ou Sorokine quitter le pays, témoignant de nouveaux rapports conflictuels entre intelligentsia littéraire et pouvoir politique. On pourra donc s’interroger sur ces modes de (dé)politisations de la littérature postsoviétique, notamment dans la perspective de 2022, qui a clairement repolarisé le champ.

Nouveaux thèmes, nouveaux acteurs, nouvelles formes ?

- Formes littéraires et récits d’expériences « minoritaires »

- Réflexions sur l’identité collective en littérature

- Hétérolinguisme au sein de textes écrits en russe

- Circulations littéraires entre la Russie et l’étranger

Alors même que le régime va en se durcissant, le monde littéraire semble, lui, se diversifier et accueillir de nouveaux thèmes et à de nouveaux acteurs/actrices (Mélat), souvent issus des jeunes générations (générations Y et X) : le développement de l’autofiction et de formes autobiographiques moins monumentales que celles des générations précédentes favorise la représentation en littérature d’expériences minoritaires : Ekaterina Manoïlo, Islam Khanipaev, Egana Djabbarova évoquent ainsi ce que c’est que d’être respectivement kazakhe, daghestanais et azerbaïdjanaise dans la Russie contemporaine ; des recueils comme Petites histoires sur la sexualité féminine (Маленькая книга истории о женской сексуальности, No Kidding Press, 2019) et la poésie de Galina Rymbu décrivent la vie des corps féminins. On voit également apparaître une littérature homosexuelle qui ne se limite pas aux quelques grands noms des années 1980, qui s’organise et devient visible. Une place notable est faite également aux langues dites minoritaires au sein de l’État russe.

Ces nouveaux territoires de la prose russe contemporaine gagneraient à être cartographiés et décrits, de façon à mettre en évidence continuité historique et ruptures.

Institutions officielles et alternatives : nouveaux lieux de la littérature

- Stratégies éditoriales individuelles (écrivain.es) et collectives (maisons d’éditions)

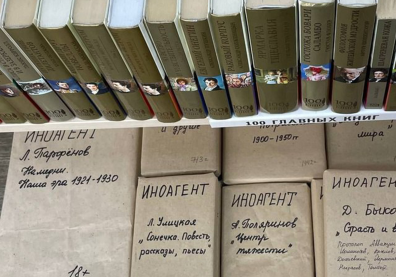

- Discours institutionnels (universités, bibliothèques, musées) sur la littérature et le rôle de l’écrivain, associations professionnelles (Российский книжный союз) et nouvelles formes de la censure

- Vers un nouvel underground ? lieux et institutions littéraires alternatifs

Enfin, on aimerait également contribuer à enrichir les études sur la littérature contemporaine russe en abordant le versant institutionnel de la question, qui est celui où le face-à-face avec le pouvoir est le plus constant. La reconfiguration du paysage éditorial russe dans la période post-soviétique puis sous Poutine a déjà été étudiée (Ostromooukhova, Mélat) : la diversification des années 1990 s’est suivi d’une consolidation autour de deux géants, Eksmo et AST, qui ont fusionné en 2012. Malgré cela, les années 2010 ont vu l’apparition de nombreuses petites maisons d’édition, parfois adossées à des librairies (Все свободные à Saint-Pétersbourg) ou à des organismes de presse (Такие дела).

On peut également s’interroger sur les positions prises par les bibliothèques, les musées littéraires, les départements de lettres, qui sont des lieux où la question de l’adhésion ou de la résistance au pouvoir se pose de façon très concrète. L’apparition d’institutions littéraires alternatives, spécifiquement en ce qui concerne l’enseignement de l’écriture littéraire (Write like a grrrl, Школа литературных практик) en parallèle du très établi institut Gorki, est également un phénomène singulier des années 2010.

Enfin, la circulation numérique des textes littéraires a connu un développement considérable depuis le 24 février 2022, mais s’inscrit dans une histoire plus longue : les plates-formes personnelles et collectives, les pages Facebook, Instagram ou Telegram d’auteur.es constituent un tiers-lieu de la littérature russe du 21ème siècle qu’il importe d’explorer à la suite de quelques études pionnières (Vejlian, Lipovetsky).

Calendrier

- Envoi des propositions (entre 300 et 500 mots) avec courte biographie à l’adresse suivante : Voir l'e-mail avant le 1er septembre 2024.

Les langues du colloque sont le français, le russe et l’anglais.

Une prise en charge des frais de transport et d’hébergement est envisagée.

Une sélection d’articles issus du colloque sera publiée dans un numéro de la revue Slavica Occitania.

Comité d’organisation :

- Sylvia Chassaing (Inalco, CREE)

- Antoine Nicolle (Inalco, CREE)

Comité scientifique :

- Isabelle Després (Université Grenoble Alpes)

- Sarah Gruszka (EHESS / Sorbonne Université)

- Hélène Mélat (Sorbonne Université)

- Bella Ostromooukhova (Sorbonne Université)

- Dany Savelli (Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès)

Bibliographie indicative

- Birgit Beumers, Alexander Etkind, Olga Gurova, Sanna Turoma (éds.), Cultural Forms of Protest in Russia, New York, Routledge, 2017.

- Marijeta Bozovic, Avant-Garde Post–: Radical Poetics After the Soviet Union, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2023.

- Isabelle Després, « Peut-on écrire l’histoire du postmodernisme russe ? » in Revue des études slaves, vol. XCIII, n°2-3, 2022, p. 301-316.

- Evgeny Dobrenko, Mark Lipovetsky (éds.), Russian Literature since 1991, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Aleksandra Konarzewska, Anna Nakai (éds.), Voicing Memories, Unearthing Identities: Studies in the Twenty-First-Century Literatures of Eastern and East-Central Europe, Wilmington, Vernon Press, 2023.

- Lena Jonson, Andrei Erofeev (éds), Russia – Art Resistance and the Conservative-Authoritarian Zeitgeist, New York, Routledge, 2018.

- Ilya Kukulin, « Cultural Shifts in Russia since 2010: Messianic Cynicism and Paradigms of Artistic Resistance » in Russian Literature, vol. 96-98, 2018, p. 221-254.

- Mark Lipovetsky, Postmodern Crises: From Lolita to Pussy Riot, Brookline, Academic Studies Press, 2017.

- Hélène Mélat, Le premier quinquennat de la prose russe, Paris, Institut d’études slaves, 2005.

- Hélène Mélat (éd.), La littérature russe à l’aube du XXe siècle, Paris, Institut d’études slaves, 2005.

- Hélène Mélat, « Vingt ans après : que sont nos espoirs devenus ? Le contexte socio-littéraire postsoviétique : 1992-2012 », in Petra James et Clara Royer (éds), Sans faucille ni marteau. Ruptures et retours dans les littératures européennes postcommunistes, Peter Lang, 2013.

- Boris Noordenbos, Post-Soviet Literature and the Search for a Russian Identity, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Bella Ostromooukhova, « Être un petit éditeur engagé dans la Russie d'aujourd'hui : Le cas de la maison d'édition Ad Marginem » in Bibliodiversity : Publishing and Globalization, n°4, 2015, p. 34-41.

- Bella Ostromooukhova, « Négocier le contrôle, promouvoir la lecture. Éditeurs indépendants face à l'État dans la Russie des années 2010 » in Bibliodiversity : Publishing and Globalization, Alliance des éditeurs indépendants, 2019.

- Aleksei Semenenko (éd.), Satire and Protest in Putin’s Russia, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

- Евгения Вежлян (Воробьева), «Современная поэзия и проблема ее “нечтения”: опыт реконцептуализации» in НЛО, n°143, 2017.

- Анна Голубкова, « Роль и значение «толстых» журналов в литературном процессе второй половины 2010-х годов » in Artikuliatsia, n°18, 2021, http://articulationproject.net/13874

- Галина Юзефович, « Невозвращенцы » in Знамя, n° 11, 2004, URL : https://magazines.gorky.media/znamia/2004/11/nevozvrashhenczy.html

- Галина Юзефович, « Литература по имущественному признаку: что читает средний класс » in Знамя, n° 9, 2005, URL : https://magazines.gorky.media/znamia/2005/9/literatura-po-imushhestvennomu-priznaku-chto-chitaet-srednij-klass.html

English version below

BEING A WRITER UNDER PUTIN

Call for papers

International conference

Inalco, Paris, March 6-7, 2025

Russia's large-scale invasion of Ukraine was seen by many as the end of an era: hopes of democratization in Russia, from their rise in the 1990s to their gradual erosion during the Putin era, are now a thing of the past. In literature, too, the tightening of censorship since February 24, 2022 and the wave of mass emigration that followed would seem to herald a return to the Soviet tripartition: censored literature (official and authorized), uncensored literature (samizdat and tamizdat), emigrated literature, with all the nuances that need to be added to such a division. However, without denying the upheaval represented by February 24, we can question the relevance of such a clear-cut periodization. The regime has been gradually tightening at least since 2011, and the Russian literary scene has reacted to this development. We might add, as Galina Youzefovich notes, that literature is a "slow-reacting art" (искусство медленного реагирования) and that the shockwaves of the war in Ukraine (and perhaps even of the one that began in 2014) are not perceived by all writers as having to call into question their practices.

This conference, therefore, aims to provide an overview of literary life from the late 1990s to the present day, putting contemporary upheavals into perspective in light of the war: what does it mean to be a writer under Vladimir Putin in 2024, compared to 1999, 2011, 2014? It is a matter of contextualization and historicizing Russian literary positionings triggered by the start of the war: February 24, 2022, rightly experienced as a major rupture, tends to obscure that the question of commitment or disengagement, personal or institutional, has in fact been posed, after the freedom of the 1990s, throughout the entire Putin period, which has been characterized by the coexistence of growing pressure on freedom of expression and a diversification of literary production.

Below are some suggestions for further reflection.

Literature as witness to post-Soviet history

- Literary memory of the recent Russian past

- Rewriting history, alternative histories of Russia and the USSR

- Echoes between personal histories/stories of everyday life and history in general

The memory of Soviet repression in contemporary literature has been the subject of several studies (Jurgenson, Platt) and its representatives are now contemporary classics (Lebedev, Yakhina, Alexievitch): they are often translated into several languages and have won numerous prizes. Meanwhile, the question of the memory of the post-Soviet period – the "crazy 1990s" (лихие девяностые), the 1993 constitutional crisis, the figure of Yeltsin, the wars in Chechnya, Putin's rise to power and the bombings of 2000 – is given much less attention, even though it forms the backdrop to intimate narratives in which public and domestic violence are echoed (Bogdanova, Vasyakina), or is the very subject of intrigue in the conspiratorial and conservative novels (Prokhanov). The depiction of the various post-Soviet wars that preceded or accompanied Vladimir Putin's rise to power (Gelasimov, Prilepine, Sadulayev) also deserves scholarly attention.

New politicizations and depoliticizations in literature

- Political stances in literature (within/outside texts)

- Ideological/political evolution of writers

- Explicit or implicit refusals to take a stand

- Networks of literary and political sociability (magazines, bookshops)

After the strong political polarization of literary magazines at the turn of perestroika, large swathes of post-Soviet literature became ostensibly depoliticized: the diversification and explosion of a literature for the masses provided a counterpoint to the capture of culture by ideology during the Soviet period. However, in the 2000s, new politicizations emerged in the literary field: the neoconservative current asserted itself, while "liberal" authors (Akunin, Bykov) took a stand in the public debate. In the 2010s, a first wave of exiles saw authors such as Akunin and Sorokin leave the country, testifying to a new conflictual relationship between the literary intelligentsia and political power. We can therefore examine the ways in which post-Soviet literature has been (de)politicized, particularly in view of 2022, which has clearly repolarized the field.

New themes, new actors, new forms?

- Literary forms and accounts of "minority" experiences

- Reflections on collective identity in literature

- Heterolingualism in texts written in Russian

- Literary circulation between Russia and abroad

At a time when the regime is hardening, the literary world seems to be diversifying, welcoming new themes and new actors (Mélat), often from the younger generations (generations Y and X): the development of autofiction and autobiographical forms that are less monumental than those of previous generations encourages the representation of minority experiences in literature: Ekaterina Manoïlo, Islam Khanipaev, Egana Djabbarova thus evoke what it is like to be Kazakh, Dagestani and Azerbaijani, respectively, in contemporary Russia; collections like Little stories about women's sexuality (Маленькая книга истории о женской сексуальности, No Kidding Press, 2019) and the poetry of Galina Rymbu describe the life of female bodies. We are also seeing the emergence of a homosexual literature that is not limited to the few big names of the 1980s but is becoming more organized and visible. The so-called minority languages of the Russian state are also making their presence felt.

These new territories of contemporary Russian prose would benefit from being mapped and described to highlight historical continuity and ruptures.

Official and alternative institutions: new literary venues

- Individual (writers) and collective (publishing houses) publishing strategies

- Institutional discourses (universities, libraries, museums) on literature and the role of the writer, professional associations (Российский книжный союз) and new forms of censorship

- Towards a new underground: alternative literary venues and institutions

Finally, we would also like to contribute to the study of contemporary Russian literature by addressing the institutional side of the question, where the face-to-face confrontation with power is most constant. The reconfiguration of the Russian publishing landscape in the post-Soviet period and then under Putin has already been studied (Ostromooukhova, Mélat): the diversification of the 1990s was followed by consolidation around two giants, Eksmo and AST, which merged in 2012. Despite this, the 2010s saw the emergence of numerous small publishing houses, sometimes backed by bookshops (Все свободные in St. Petersburg) or press organizations (Такие дела).

We might also consider the positions taken by libraries, literary museums and literature departments at universities, which are places where the question of adherence to or resistance to power is posed in a very concrete way. The emergence of alternative literary institutions, specifically for teaching literary writing (Write like a grrrl, Школа литературных практик) alongside the established Gorky Institute, is also a singular phenomenon of the 2010s.

Finally, the digital circulation of literary texts has seen considerable development since February 24, 2022, but is part of a longer history: personal and collective platforms, Facebook, Instagram or Telegram pages of writers constitute a third place of Russian literature in the 21st century that it is important to further explore following some pioneering studies (Vejlian, Lipovetsky).

Timeline

- Proposals (between 300 and 500 words) and short biography to be sent to the following address: Voir l'e-mail by September 1, 2024.

The conference will take place in French, Russian, and English.

Travel and accommodation expenses will be covered.

A selection of the presented papers will be published in a special journal issue.

Organizing committee:

- Sylvia Chassaing (Inalco, CREE)

- Antoine Nicolle (Inalco, CREE)

Scientific committee:

- Isabelle Després (Université Grenoble Alpes)

- Sarah Gruszka (EHESS / Sorbonne Université)

- Hélène Mélat (Sorbonne Université)

- Bella Ostromooukhova (Sorbonne Université)

- Dany Savelli (Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès)

Текст на русском языке ниже

БЫТЬ ПИСАТЕЛЕМ ПРИ ПУТИНЕ

Призыв к написанию статей

Международная конференция

Иналко, Париж, 6-7 марта 2025 г.

Масштабное вторжение России в Украину многие восприняли как конец эпохи: надежды на становление демократии в России, которые возродились в 90-е годы, разрушились в эпоху правления Путина. Параллельно в прессе и в литературе, начиная с 24 февраля 2022, наблюдалось все растущее ожесточение цензуры и как следствие волна массовой эмиграции как писателей, так и других деятелей культуры. Казалось бы, снова ждет возврат к советскому трехчастному делению: цензурная литература (официальная и авторизованная), неподцензурная литература (самиздат и тамиздат), эмигрантская литература, со всеми нюансами, которые необходимо добавить к такому делению.

Однако такое строгое деление может быть поставлено под сомнение, несмотря на потрясении, которыми ознаменовалось 24 февраля. Действительно, режим переживал постепенное ужесточение уже с 2011 года, а русский литературный мир неизбежно реагировал на это развитие событий. Как отмечает Галина Юзефович: литература — это искусство медленного реагирования, и шоковые волны войны на Украине (и, возможно, даже войны, начавшейся в 2014 году) не всеми писателями воспринимаются как ставящие под вопрос их творческую практику.

В этой связи данная конференция ставит своей целью - сделать обзор перемен в литературной жизни в период с конца 1990-х годов до наших дней, рассматривая современные потрясения в свете войны. Будут рассмотрены такие вопросы как: что значит быть писателем при Владимире Путине в 2024 году? Что в день сегодняшний отличает литературное поприще от его же в 1999, 2011 или 2014? Задача конференции состоит в том, чтобы придать контекст и историю позициям российских литературных деятелей, вызванным началом войны: (восприятие событий после?) 24 февраля 2022 года, справедливо рассматриваемое как решительный перелом, имеет тенденцию скрывать тот факт, что вопрос о личной или институциональной приверженности или размежевании фактически возникал после свободы 1990-х годов на протяжении всей путинской эпохи, которая характеризовалась сосуществованием растущего давления на свободу слова и разнообразия литературного производства.

Ниже приведены некоторые предложения для дальнейших размышлений.

Литература как свидетель постсоветской истории

- Литературная память о недавнем российском прошлом

- Переписывая историю: альтернативная история России и СССР

- Параллели между частными жизнями и историей в целом

Если память о советских репрессиях в современной литературе была предметом нескольких исследований (Юргенсон, Платт), а ее представители стали современными классиками (Лебедев, Яхина, Алексиевич), то вопросам памяти о постсоветском периоде, о «безумных 1990-х», конституционном кризисе 1993 года, фигуре Ельцина, войне в Чечне, приходе к власти Путина и терактах 2000 года, уделяется гораздо меньше внимания. Однако, именно эти события являются основным фоном, в котором протекали частные жизни и развивались личные истории. Вероятно, именно поэтому мы обнаруживаем следы общественного и домашнего насилия в произведениях Богдановой, Васякиной. А порой эти темы становятся центральным сюжетом в романах Александра Проханова. Кроме того, отдельного внимания и углубленного исследования заслуживают произведения (Геласимов, Прилепин, Садулаев), в которых содержатся свидетельства различных постсоветских войн, предшествовавших или сопровождавших приход к власти Владимира Путина.

Политизация и деполитизация литературы

- Политические взгляды в литературе (внутри/вне текстов)

- Эволюция писателей (политических взглядов/идеологий)

- Явный или скрытый отказ от выражения политической позиции

- Литературные и окололитературные пространства для обмена политическими взглядами (журналы, книжные магазины)

В результате значительной вовлеченности литературных журналов в вопросы политики в период перестройки, значительная часть постсоветской литературы, напротив, стала демонстративно деполитизированной. Так, всплеск и разнообразие литературы для масс явилось противовесом идеологическому захвату культуры в советский период. Однако, в 2000-ых в культурном пространстве появились новые литературные полюсы, а именно: неоконсервативное направление укрепилось, а «либеральные» авторы (Акунин, Быков) заняли свою позицию в общественных дебатах. В 2010-х годах Россия пережила первую волну «новой» эмиграции, а ее представители, такие авторы как Акунин и Сорокин, отразили новую форму конфликтных отношений между пишущей интеллигенцией и властью. В этой связи интересно изучить способы (де)политизации постсоветской литературы, в том числе в преддверии 2022 года, который стал переломным в рассматриваемом контексте.

Иные сюжеты, новые действующие лица, неожиданные формы?

- Литературные формы и рассказы о переживаниях "меньшинств"

- Размышления о коллективной идентичности в литературе

- Гетеролингвизм в русскоязычных текстах

- Литературная миграция между Россией и зарубежьем

В то время как режим становится все жестче, литературный мир, кажется, в противовес этому диверсифицируется и принимает новые темы и новых актеров (Мела), часто из молодых поколений (поколений Y и X). Так, новое развитие получают автофикшн и автобиографическая форма. То есть формы куда менее монументальные, чем у предыдущих поколений. Поощряется представление опыта меньшинств в тексте: Екатерина Манойло, Ислам Ханипаев и Эгана Джаббарова рассказывают о том, каково быть казахом, дагестанцем и азербайджанцем в современной России; сборники «Маленькие истории женской сексуальности» и поэзия Галины Рымбу описывают жизнь женского тела. Наблюдается также выраженное присутствие литературы, поднимающей темы гомосексуальности, которая не ограничивается несколькими громкими именами как это было в 80-ые годы, а становится организованным течением. Кроме того, заметными становится так называемые миноритарные языки российского государства.

Эти новые территории, где получают развитие новые формы современной русской прозы, было бы полезно нанести на карту и выявить следы культурной и исторической преемственности или же их отсутствие.

Официальные и альтернативные институты: новые литературные территории

- Индивидуальные (писатели) и коллективные (издательства) издательские стратегии

- Институциональный дискурс (университеты, библиотеки, музеи) о литературе и о роли писателя, профессиональные ассоциации (Российский книжный союз) и новые формы цензуры

- К новому андеграунду: альтернативные литературные площадки и институции

Наконец, мы хотели бы внести свой вклад в изучение современной русской литературы, обратившись к институциональной стороне вопроса, где противостояние с властью носит наиболее выраженный характер, протяженный о времени. Изменение конфигурации российского издательского ландшафта в постсоветский период и при Путине уже изучались (Остромоухова, Мела): за диверсификацией 1990-х последовала консолидация вокруг двух гигантов, «Эксмо» и «АСТ», которые слились в 2012 году. Несмотря на это, в 2010-х годах появилось множество небольших издательств, иногда поддерживаемых книжными магазинами («Все свободны» в Санкт-Петербурге) или СМИ-организациями («Такие дела»).

Особое внимание стоит уделить позиции библиотек, литературных музеев и литературных факультетов — все это места, где вопрос о поддержке или сопротивлении власти ставится «ребром». Появление альтернативных литературных институтов, специально предназначенных для обучения писательскому искусству (Write like a grrrl, Школа литературных практик), наряду с уже устоявшимся Институтом Горького, также является своеобразным явлением 2010-х годов.

Наконец, распространение литературных текстов после 24 февраля 2022 года все больше стало принимать цифровую форму. Однако, этот процесс также является частью другой более длительной истории: развитие персональных и коллективных платформ, популяризация посредством страниц авторов в Facebook, Instagram или Телеграме, которые занимают почетное третье место в XXI веке в борьбе за распространение текста, что также важно изучить след за новаторскими исследованиями Вежлян и Липовецкого.

Организационный комитет:

-

Сильвия Шассен (Inalco, CREE)

-

Антуан Николь (Inalco, CREE)

-

Научный комитет:

- Изабель Депре (Университет Гренобль Альпы)

- Сара Грушка (EHESS / Университет Сорбонны)

- Белла Остромоухова (Университет Сорбонны)

- Дани Савелли (Университет Тулузы Жан Жорес)